Cerebral Bypass Surgery: What the Patient Needs to Know

Why should you have your surgery with Dr. Cohen?

Dr. Cohen

- 7,000+ specialized surgeries performed by your chosen surgeon

- Prioritizes patient interest

- More personalized care

- Extensive experience = higher success rate and quicker recovery times

Major Health Centers

- No control over choosing the surgeon caring for you

- One-size-fits-all care

- Less specialization

For more reasons, please click here.

Overview

Cerebral bypass surgery is a procedure to restore blood flow to the brain by redirecting blood around blocked, narrowed, or damaged arteries. The operation uses a blood vessel from another part of the body or reroutes a donor artery from the scalp onto the brain. The arteries are surgically joined with sutures to supplement or replace blood flow in that area. Complications specific to cerebral bypass surgery include stroke due to manipulation of the blood vessels and temporary clamping of them during the procedure.

What Is Cerebral Bypass Surgery?

Cerebral bypass surgery is a procedure to restore blood flow to the brain by redirecting blood around blocked, narrowed, or damaged arteries. This can be performed to supplement blood flow when small arteries are narrowed (“low-flow” bypass) or replace blood flow when medium-to-large blood vessels need to be sacrificed during complex brain surgeries (“high-flow” bypass).

Figure 1. Cerebral bypass surgery involves joining the donor and recipient arteries together with sutures so that blood can bypass the blocked area and flow in adequate amounts to the brain.

When additional blood flow is needed, an artery from the scalp or face is detached from its normal position at its end, rerouted into the skull, and connected to an artery on the surface of the brain. This method is usually performed for diseases that cause narrowing of the arteries (for example, internal carotid artery stenosis or Moyamoya disease). It may also be used when the removal of complex aneurysms or tumors requires sacrifice of brain blood vessels during the operation.

When blood flow needs to be replaced, a piece of artery or vein is obtained from another part of the body (vessel graft). Usually, vessel grafts are taken from the saphenous vein in the leg or the radial artery in your nondominant arm. The graft is attached to the artery before and after the area of blockage to reroute blood. This may be performed when larger blood vessels must be sacrificed during complex aneurysm or tumor removal.

STA–MCA Bypass

The superficial temporal artery (STA) to middle cerebral artery (MCA) bypass is the most widely used technique to supplement blood flow to the brain. The pulse that you feel when you place your hands on your temples comes from the STA. The STA supplies blood to the temples and scalp and divides into 2 branches. The larger branch is disconnected at its end and reattached to the MCA on the surface of the brain. Currently, STA–MCA bypasses can be used for the following:

- Reduced blood flow and delivery of oxygen to the brain (cerebral ischemia) that cannot be treated by other medical methods

- Moyamoya disease

- Complex intracranial aneurysms

- Complex skull base tumors

In an STA–MCA bypass, an artery from outside the skull (STA) must be connected to an artery inside of the skull and on the brain (MCA). Thus, this is also called an extracranial–intracranial (EC-IC) bypass.

Who Performs Cerebral Bypass Surgery?

Cerebral bypass surgery is performed by a neurosurgeon who has specialized training in cerebrovascular surgery.

What Happens Before Cerebral Bypass Surgery?

Before cerebral bypass surgery, several imaging techniques will be used to determine if cerebral bypass surgery is necessary and possible and to plan for the procedure. The imaging sources are of 3 main types:

- Structural: This imaging includes magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to check the brain for any structural abnormalities. Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) is a type of MRI sequence especially useful for detecting areas of the brain that are not getting enough blood and oxygen. The pattern seen on DWI can also give surgeons a clue as to if the cause is due to sudden blocking or narrowing of an artery.

- Angiography: This test visualizes blood flow to check if the donor and recipient arteries are open and unobstructed. Information from an angiography can be used to determine the diameter of the blood vessels that will later be joined together. In addition, angiography can be used to check for small surrounding blood vessels (collateral circulation) that might be able to deliver enough oxygen to the area. If collateral circulation is sufficient, a cerebral bypass might not be necessary.

- Perfusion: This imaging includes PET, xenon computed tomography (CT), CT perfusion, MR perfusion, and single-photon emission CT. These are useful for determining how successful collateral blood vessels are at overcoming the lack of blood flow from the blocked artery. Perfusion imaging can be used to employ challenge tests (for example, acetazolamide test or balloon occlusion test). These tests reduce blood flow in a certain area and then check to determine if surrounding collateral blood vessels widen (dilate) to provide more blood to the area in response.

If a cerebral bypass will be performed, the surgeon will explain what the procedure will entail along with its risks and its benefits. You will fill out consent forms and other paperwork to inform the surgeon of relevant medical history such as allergies, other medications you are taking, reactions to anesthesia, and any previous surgeries.

One week before surgery, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen (for example, Advil or Motrin), naproxen (for example, Aleve), or another prescribed NSAID as well as blood thinners such as warfarin (for example, Jantoven or Coumadin) and clopidogrel (for example, Plavix) should be stopped to decrease the risk of bleeding. This is not an all-inclusive list. Inform your physician of all medications and supplements that you are taking, and follow his or her recommendations.

Several days before surgery, a physical examination, blood tests, an electrocardiogram, chest X-rays, and other tests might be performed to ensure that your body can safely handle the surgery and that surgical scenarios (for example, bleeding) are properly prepared for. A baseline neurological examination is conducted and repeated after surgery.

On the night before or morning of the surgery, your physician might ask you to not eat or drink anything (fasting) to prevent vomiting while under general anesthesia. You might also be asked to shower or wash your hair with a special antiseptic shampoo, which helps to reduce the possibility of infection at the site of incision.

What Happens During Cerebral Bypass Surgery?

Cerebral bypass surgery can take 3 to 5 hours depending on your underlying condition. Steps for the commonly performed STA–MCA bypass are described below.

Step 1: Patient Preparation

The patient is placed on the operating table and given general anesthesia. After the patient is asleep, a 3-pin skull clamp is connected to the table and the patient’s head to immobilize it during the procedure. A miniDoppler probe can detect the pulse of the artery and is used to mark the route of the STA and its branches.

Figure 2. While under general anesthesia, the patient’s head is positioned and immobilized with a 3-pin skull clamp. Using a miniDoppler probe, the route of the dominant STA branch is mapped (left) and the path of the incision is marked (right).

Blood pressure must be tightly controlled during the surgery. A needle with a blunt end (cannula) is inserted into an artery in the arm. This is connected to an electronic monitor that will constantly display blood pressure on a graph. A tube is placed in a large vein (central venous catheter) to quickly deliver blood, medications, or other fluids if needed.

Step 2: Harvesting the Donor Artery

The scalp is cut carefully and not too deeply along the incision line to preserve the artery. A branch of the STA is carefully dissected from its surroundings.

Figure 3. The surgeon carefully cuts into the scalp without injuring the STA branch. (Left) Curved forceps are used to dissect over the artery gently and bluntly. (Right) Sutures are used to retract the layers of the scalp.

Step 3: Dissecting the Recipient Artery

A craniotomy is performed and an approximately 6-cm bone flap is elevated. The surgeon chooses the best MCA branch as the recipient artery based on its accessibility, diameter, and caliber. The length of the donor STA branch is measured to ensure that it can reach the recipient artery without tension. After the recipient artery is selected, the beginning of the STA is clamped using a temporary clip, and its end is cut obliquely, or “fish-mouthed,” to prepare it for surgical connection (anastomosis) with the MCA recipient branch. A diamond-shaped cut is made on the recipient MCA branch.

Figure 4. (Left) The beginning of the STA is clamped to ensure that blood does not flow out through the cut end. (Right) The MCA branch is also clamped on both sides to prevent blood from flowing through the artery while a diamond-shaped cut is made.

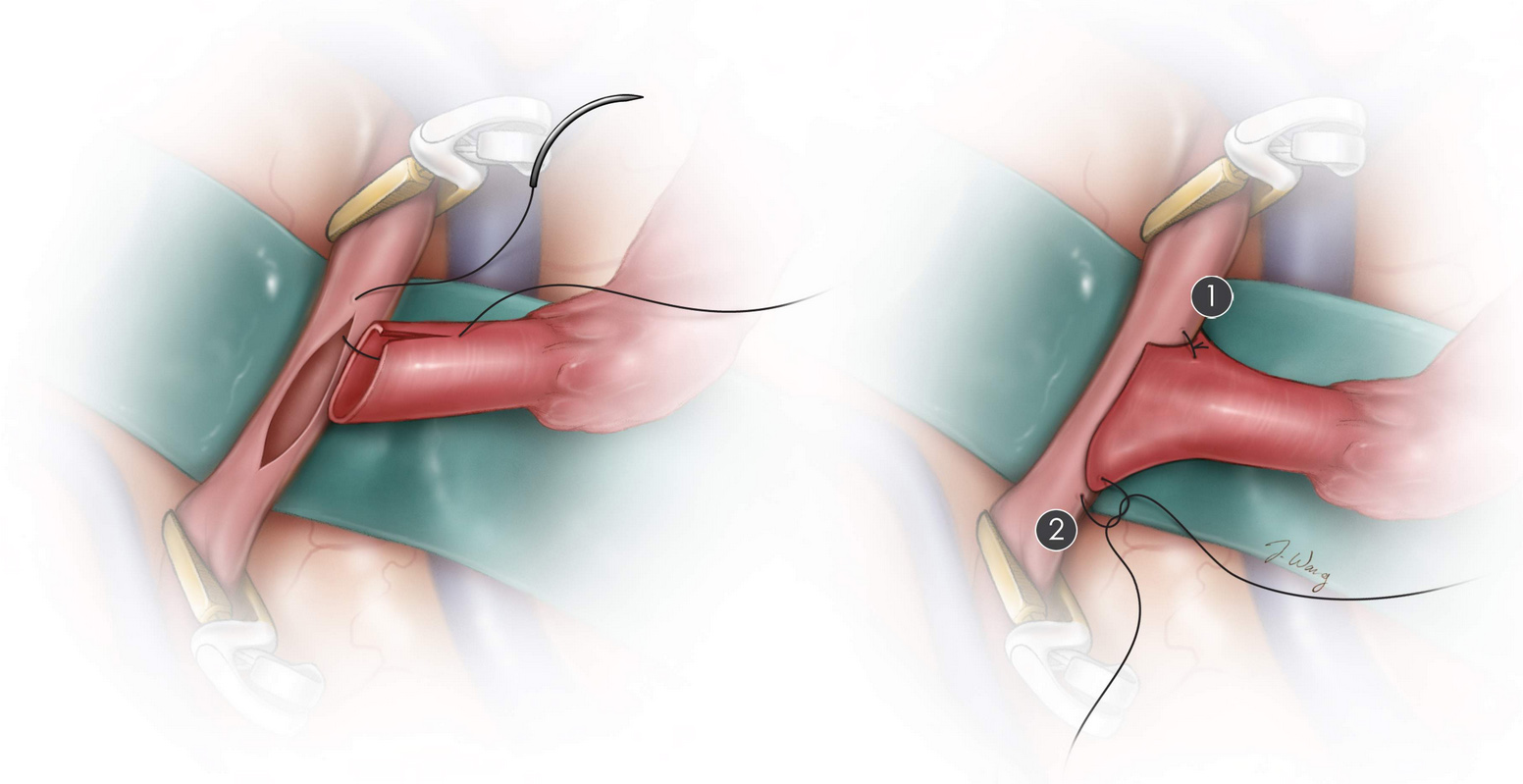

Step 4: Anastomosis

The STA and MCA are surgically joined using sutures. After the initial sutures are placed on the “heel” and “toe” of the joined arteries, the sides are secured using additional sutures. When the connection is secured, the clips are removed in an orderly fashion. If significant leakage is present at the connection site, additional sutures can be placed.

Figure 5. (Top) The initial sutures of the anastomosis are illustrated. (Bottom) The final product of the STA–MCA bypass is displayed.

Step 5: Closure

Unlike a normal craniotomy closure, which completely sutures the dura back together and replaces the entire bone flap, closure after an STA–MCA bypass requires the presence of a small bony opening so that the STA branch can travel from the inner aspect of the scalp, through the bone, to the inside of the brain where the MCA resides. The bone flap with a small opening for the STA is reattached to the rest of the skull using small metal plates and screws.

In this video, Dr. Cohen describes the techniques for a superficial temporal artery to middle cerebral artery (STA-MCA) bypass.

For more information about the technical aspects of the surgery and extensive experience of Dr. Cohen, please refer to the chapter on Low Flow Revascularization in the Cerebrovascular Surgery section of the Neurosurgical Atlas.

What Happens After Cerebral Bypass Surgery?

Immediately after cerebral bypass surgery, you are taken to a recovery room where you are monitored as the anesthesia wears off. You may feel discomfort at the site of the incision and a sore throat from the tube that was used to assist your breathing. Once awake, you are taken to the intensive care unit (ICU) for further monitoring and pain control.

The pulse of the STA is monitored daily using a bedside microDoppler device, which checks if the connection between the STA and MCA is working. Aspirin is often started and continued indefinitely. Frequent neurologic exams are conducted. The medical staff may examine your pupils with a flashlight and ask you to move your arms and legs to check for signs of brain injury.

Once your condition has stabilized, you are transferred to the regular hospital ward. Getting out of bed and walking as tolerated is encouraged, and a physical therapist might be asked to work with you. Depending on the complexity of the operation, the total hospital stay is 1 to 2 days.

At home, you should follow the instructions provided by your surgeon. A follow-up appointment might be made in the next 1 to 2 weeks. Headaches that are described as pulsating or pounding are common and can persist for several months after surgery. In general, avoid high-intensity activities, keep the incision site clean, and take pain medicines as directed. Discuss when you can return to work with your physician. You might not be able to return to work for several weeks.

Activities

- Avoid strenuous activity (for example, lifting heavy items [>5 lbs], jogging, sex)

- Avoid risky activities that require your attention (for example, driving)

- Do not drink alcohol or use nicotine products (for example, smoking, vaping)

- Try to walk 5 to 10 minutes/day, and gradually increase this time as you recover

- Sleep with your head elevated and apply ice 3 times/day for 15 minutes to reduce pain and swelling

- Drink water and eat foods high in fiber to resolve constipation caused by the narcotics used for pain control during or after surgery

- Discuss activities such returning to work or air travel with your physician

Incision Care

- Shower as early as the day after surgery

- Gently wash the incision site with soap and water daily

- Avoid hair styling products, lotions, and baths for 1 month after surgery

- Use gauze to pad the area between the incision and your glasses

Medications

- Take acetaminophen (Tylenol) for headaches and other pain medications as directed by your physician

- You will be recommended to take antiplatelet medication (for example, aspirin) daily to thin the blood and prevent clots from forming

When to Call Your Doctor

- Fever or chills

- Redness, swelling, bleeding, increased pain around the incision site

- Swelling at the incision site with clear fluid leaking from your ears or nose

- Excessive sleepiness, confusion, increased headaches, weakness in your arms or legs

- Vision, speech, or breathing problems

- Swelling in the calf of one leg

- Seizures

Call 911 if you experience trouble breathing, signs of a stroke (facial droop, slurred speech, weakness, confusion), or a sudden and severe headache (possible aneurysm rupture).

What Are the Possible Complications?

Complications of cerebral bypass surgery can include general complications of surgery such as nausea and vomiting from anesthesia, pain at the craniotomy site, seizures, swelling and bruising of the face, infection, and bleeding. Stroke can occur due to the manipulation of arteries and temporary clipping of them during the operation or if the surgical connection between the arteries does not work properly.

What Is the Recovery Outlook?

Cerebral bypass surgery aims to provide additional blood flow or to replace blood flow to areas that are lacking adequate blood delivery in the brain. This helps to reduce the risk of strokes but does not cure the underlying condition. The effectiveness of cerebral bypass surgery depends on the quality of the donor vessel and the disease being treated.

Cerebral bypass surgery for patients with carotid artery occlusion is still controversial because several clinical trials have failed to show a clear benefit over medical management. However, a select subset of patients who have exhausted all other options might benefit from this procedure.

Cerebral bypass surgery for patients with moyamoya disease has been shown to provide clear benefit in several studies. Adults and older children with moyamoya disease are more likely to undergo and benefit from the STA–MCA procedure because they have larger vessels for anastomosis than younger children. As much as 91.8% of patients presenting with brief stroke-like attacks (transient ischemic attacks) were free of them 1 year later.

After cerebral bypass surgery, the long-term outcomes depend on taking medications as directed by your physician and living a healthy lifestyle by eating a healthy diet and exercising regularly.

Glossary

Anastomosis—connection between adjacent blood vessels

Artery—blood vessel that delivers oxygen-rich blood from the heart to your tissues

Craniotomy—procedure to open and remove a piece of bone from the skull to expose the brain

Bone flap—section of bone temporarily removed during a craniotomy

Dura mater—outermost covering of the brain

Cannula—needle with a blunted end

Cerebral ischemia—reduced blood flow and delivery of oxygen to the brain

Cerebrospinal fluid—clear fluid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord

Collateral circulation—small blood vessels that open to provide alternative blood circulation around a blocked artery

Seizure—sudden burst of abnormal electrical activity in the brain that leads to uncontrollable spasms, twitching, or jerking

Stroke—damage to the brain caused by reduced or interrupted blood supply

Suture—stitch or row of stitches that hold together the edges of a wound or surgical cut

Vein—blood vessel that delivers deoxygenated blood from tissues back to the heart

Vessel graft—blood vessels taken from another part of the body and used for the bypass procedure

Contributor: Gina Watanabe BS

References

- Guzman R, Lee M, Achrol A, et al. Clinical outcome after 450 revascularization procedures for moyamoya disease. J Neurosurg 2009;111:927–935. doi.org/10.3171/2009.4.JNS081649

- EC/IC Bypass Study Group. Failure of extracranial-intracranial arterial bypass to reduce the risk of ischemic stroke. Results of an international randomized trial. N Engl J Med 1985;313:1191–1200. doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198511073131904

- Esposito G, Amin-Hanjani S, Regli L. Role of and Indications for bypass surgery after carotid occlusion surgery study (COSS)? Stroke 2016;47:282–290. doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.008220