Overview of Craniopharyngioma

Why should you have your surgery with Dr. Cohen?

Dr. Cohen

- 7,000+ specialized surgeries performed by your chosen surgeon

- Prioritizes patient interest

- More personalized care

- Extensive experience = higher success rate and quicker recovery times

Major Health Centers

- No control over choosing the surgeon caring for you

- One-size-fits-all care

- Less specialization

For more reasons, please click here.

Overview

Craniopharyngiomas are relatively benign and slow-growing tumors that occur near the pituitary gland and hypothalamus around the center of the brain. Common symptoms include headaches, vomiting, and vision problems. Hormone deficiencies that lead to poor growth or absent puberty might also be found in children and adolescents.

Treatment options include surgery, radiation, or both. Although patients with a craniopharyngioma have an excellent survival rate, this tumor’s tendency to adhere to important parts of the brain and prevent complete resection leads to tumor recurrence. Therefore, patients with this type of tumor must undergo regular magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) follow-up scans. A multidisciplinary team of specialists in endocrinology, psychology, oncology, neurosurgery, and ophthalmology might be involved to maximize and maintain wellness before, during, and after treatment.

What Is a Craniopharyngioma?

A craniopharyngioma is a relatively benign and slow-growing tumor that occurs near the pituitary gland and hypothalamus in the brain. These structures are critical for the production and release of various hormones that control everything from appetite to growth. Because they often grow slowly, craniopharyngiomas that cause problems might be large at the time of diagnosis. Nearby structures such as the optic nerves, pituitary gland, and hypothalamus could be compressed and lead to symptoms.

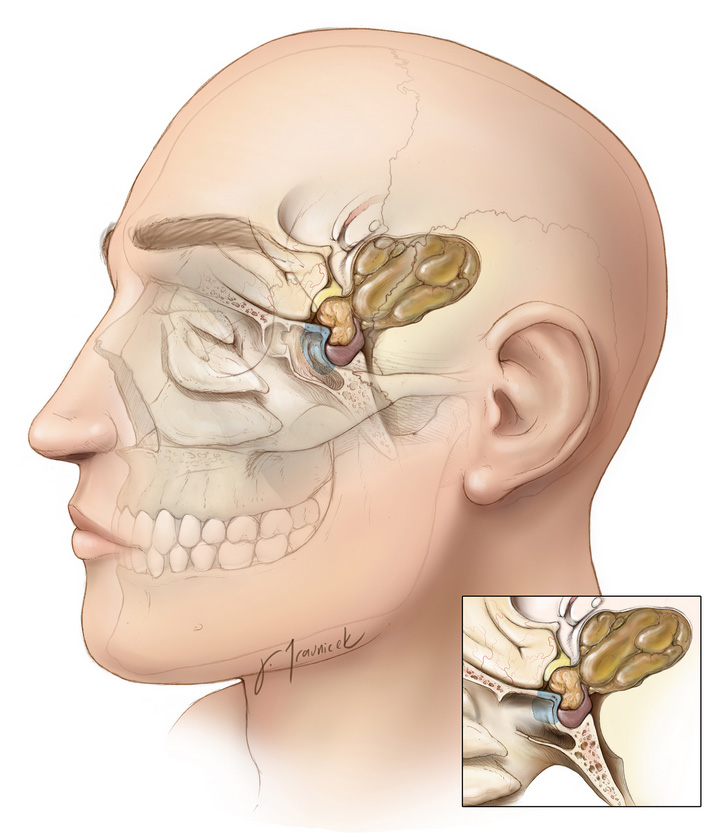

Figure 1: A craniopharyngioma (yellow brown) sitting at the base of the skull on top of the pituitary gland. A characteristic cystic component extends toward the middle of the brain.

What Are the Symptoms?

The most common symptoms are headaches, vomiting, and vision problems. Other possible symptoms include confusion, extreme thirst and urination (diabetes insipidus), feeling tired, loss of appetite, weight changes, and problems with thinking or learning.

Patients might also have various hormone abnormalities that happen for months or years before the presentation of other symptoms. Growth hormone deficiency, which leads to slowed growth that is more noticeable in children, is the most common abnormality. Gonadotropin hormone deficiency can lead to absent or halted puberty in older children and teens.

What Are the Causes?

Craniopharyngiomas currently do not have a well-defined cause or associated risk factor. Researchers believe that craniopharyngiomas might arise from abnormal development of cells that form parts of the pituitary gland in the growing fetus.

How Common Is It?

Craniopharyngiomas are very rare and affect fewer than 2 people per million each year. They mostly affect children aged 5 to 14 years and adults aged 50 to 75 years, and they account for 1% to 3% of all brain tumors.

How Is It Diagnosed?

Craniopharyngiomas are usually diagnosed by MRI. Computed tomography (CT) is used to evaluate the anatomy of the underlying skull before surgery and to view the composition of the tumor.

Craniopharyngiomas are often a mix of cysts and solid tissues but can be mostly cystic or solid. The adamantinomatous subtype is the childhood variant that consists of cysts with areas of calcification. The papillary subtype is more solid and lacks calcification.

What Are the Treatment Options?

Craniopharyngiomas are treated primarily with surgery and radiotherapy, but observation might be preferred for incidental tumors that do not cause symptoms.

Figure 3: Transnasal (left and middle) and transcranial (right) approaches for removing a craniopharyngioma.

Observation

Incidentally diagnosed tumors that cause no symptoms might be observed over time.

Surgery

Surgery for craniopharyngiomas is often the initial method of choice because most tumors are large and causing symptoms by the time they are diagnosed. This method can remove the tumor completely or partially. Partial removal will decrease tumor size and resolve symptoms associated with it. However, radiation is recommended to prevent recurrence.

In some cases, complete removal of the tumor is possible but might result in a need for the patient to undergo lifelong hormone-replacement therapy. Many consider craniopharyngiomas a chronic condition because they tend to recur even if they have been removed completely. Patients with a craniopharyngioma must undergo regular MRI follow-up scans to ensure that the tumor is not growing. After surgery, the patient is observed in the intensive care unit overnight. Depending on the complexity of the surgery, patients could stay in the hospital for 1 week or longer.

There are 2 main surgical approaches, and the patient and his or her physician should discuss which is best:

Transnasal—this approach is used when the tumor is generally localized at the midline and base of the brain. Surgical instruments are inserted through the nose to remove pieces of bone at the base of the skull and expose the craniopharyngioma. The tumor is then gently dissected from surrounding structures and pulled out. This approach is less invasive than the transcranial option.

Transcranial—this approach can be used for larger or more complex tumors. A surgical opening into the skull (craniotomy) is performed to reach the brain. Once the tumor is reached, it is dissected and removed.

One of the more frequent complications after surgery is excessive thirst and urination (diabetes insipidus), which can be treated with medication. In most cases, this complication is temporary. Other possible complications include brain fluid (cerebrospinal fluid) leakage, lack of hormone secretions, and a strong sensation of hunger (hyperphagia) leading to obesity.

In this video, Dr. Cohen describes the techniques of an endonasal approach to treat a craniopharyngioma.

For more information about the technical aspects of the surgery and extensive experience of Dr. Cohen, please refer to the chapter on Craniopharyngioma in the Neurosurgical Atlas.

Radiation

Radiation is another option for treating craniopharyngiomas, and it is often used in combination with surgery. This treatment can be delivered in 1 of 2 ways, radiosurgery (in which 1 large dose of radiation is aimed at the tumor) and fractionated radiotherapy (in which multiple small doses of radiation are delivered over several weeks). This procedure is noninvasive and requires no hospital stay for recovery. Specialized radiotherapy technologies such as proton beam therapy and intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) might be used for more precise targeting of the radiation beam to avoid nearby healthy tissues.

In radiosurgery, hundreds of small, concentrated beams of radiation are aimed at the tumor using 1 of the 3 currently available radiosurgical devices (Gamma Knife, Cyber Knife, or Novalis). The procedure itself takes 30 to 50 minutes. On the day of the procedure, the patient is placed in a stereotactic headframe, which stabilizes the head and enables the treatment team to calibrate the machine to the patient’s head and tumor. This is used in rare cases when the tumor is well separated from surrounding sensitive structures, such as the optic nerves.

Patients who undergo fractionated radiotherapy receive smaller doses of radiation over several visits. Each visit takes only 5 to 15 minutes, and the patient is able to go about his or her business before and after the visit. Fractionated radiotherapy is usually performed for residual or recurrent craniopharyngiomas.

It is important to note that radiation therapy does not remove the tumor. It might, in some cases, cause the tumor to shrink. The main goal of radiation is to stop the tumor from growing. As a result, the patient must return for MRI scans every year to check for any new growth.

Possible complications of radiation therapy include visual loss and pituitary hormone abnormalities. Radiation-induced optic neuropathy is a late complication of radiotherapy that results in sudden, painless vision loss in one or both eyes. This complication is rare but can occur months to years after treatment.

What Is the Recovery Outlook?

The current survival rate for patients with craniopharyngioma is favorable, with up to 90% of adults and children surviving at 10 years. However, long-term complications such as vision loss and abnormal hormone functioning might decrease quality of life. Recurrence can occur in nearly one-third of patients but can be treated with radiation. A multidisciplinary team of specialists in endocrinology, psychology, oncology, and ophthalmology might also be involved to maximize and maintain wellness after treatment.

Resources

American Brain Tumor Association

Pediatric Brain Tumor Foundation

Children’s Brain Tumor Foundation

American Childhood Cancer Organization

Glossary

Craniotomy—procedure to open and remove a piece of bone from the skull to expose the brain

Diabetes insipidus—condition in which the kidneys are not able to concentrate urine, usually because of insufficient production of antidiuretic hormone

Contributor: Gina Watanabe BS

References

- Karavitaki N, Brufani C, Warner JT, et al. Craniopharyngiomas in children and adults: systematic analysis of 121 cases with long-term follow-up. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2005;62:397–409. doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2265.2005.02231.x.

- Bülow B, Attewell R, Hagmar L, et al. Postoperative prognosis in craniopharyngioma with respect to cardiovascular mortality, survival, and tumor recurrence. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1998;83:3897–3904. doi.org/10.1210/jcem.83.11.5240.

- Zaidi HA, Chapple K, Little AS. National treatment trends, complications, and predictors of in-hospital charges for the surgical management of craniopharyngiomas in adults from 2007 to 2011. Neurosurg Focus 2014;37:E6. doi.org/10.3171/2014.8.FOCUS14366.

- Bakhsheshian J, Jin DL, Chang K-E, et al. Risk factors associated with the surgical management of craniopharyngiomas in pediatric patients: analysis of 1961 patients from a national registry database. Neurosurg Focus 2016;41:E8. doi.org/10.3171/2016.8.FOCUS16268.