Craniotomy: What the Patient Needs to Know

Why should you have your surgery with Dr. Cohen?

Dr. Cohen

- 7,000+ specialized surgeries performed by your chosen surgeon

- Prioritizes patient interest

- More personalized care

- Extensive experience = higher success rate and quicker recovery times

Major Health Centers

- No control over choosing the surgeon caring for you

- One-size-fits-all care

- Less specialization

For more reasons, please click here.

Overview

A craniotomy is a relatively routine neurosurgical procedure to cut and temporarily remove a piece of skull bone to access the brain. This is usually the first step before a more complex operation on the brain can be performed. After surgery, the bone flap is reattached to the skull with metal (titanium) plates and screws. The bone heals in place over the next few months (like any other broken bone).

Complications specific to the craniotomy can include pulsating or pounding headaches, jaw stiffness, a dent at the site of the craniotomy, cerebrospinal fluid leak, and blood clots.

What Is a Craniotomy?

A craniotomy is a surgical procedure to cut and temporarily remove a piece of skull bone (bone flap) to access the brain. After brain surgery, this bone flap is reattached to the skull at its original location with small metal plates and screws. Over time, the bone heals just like any other broken bone.

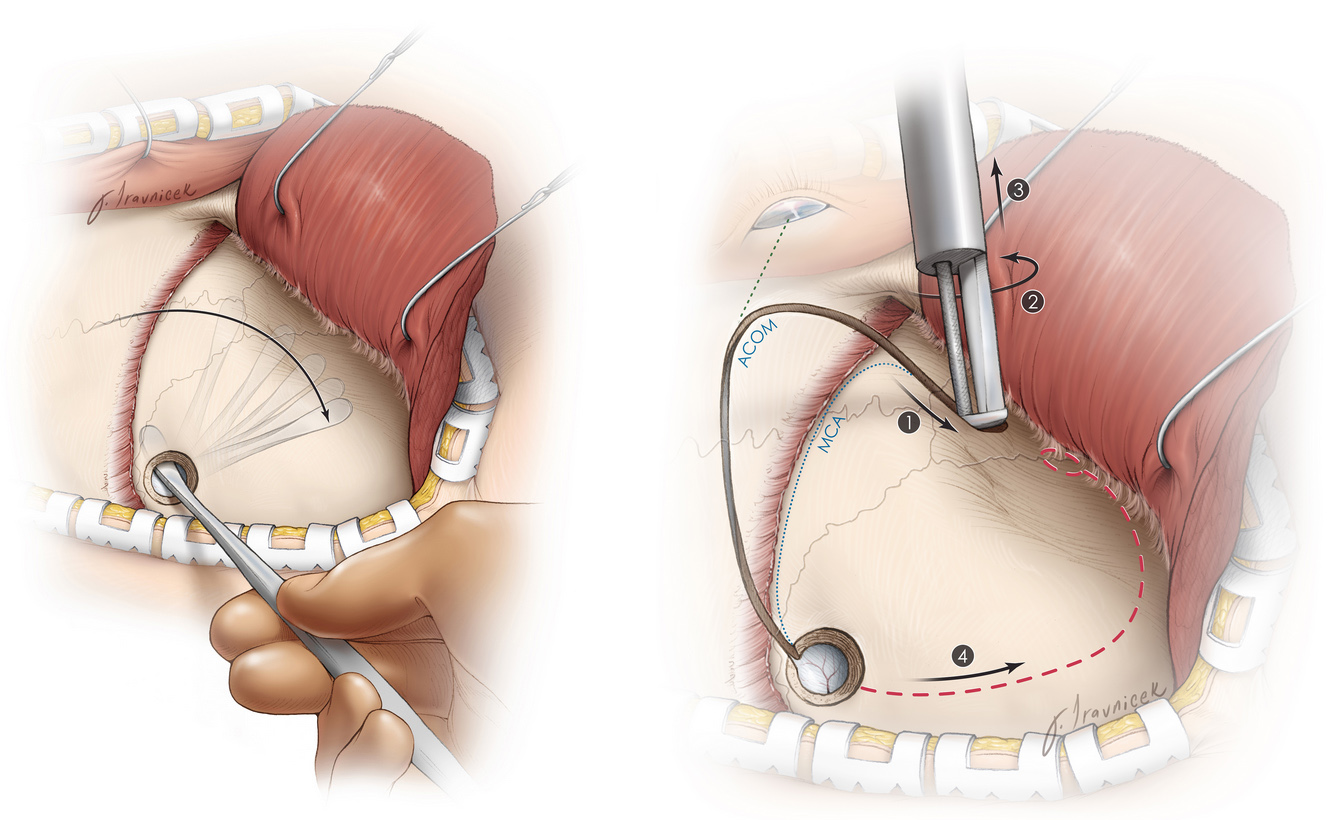

Figure 1. A special saw called a craniotome is used to cut through the bone (left), and this bone flap is temporarily removed to access the brain during surgery (right).

Craniotomies can vary in location and size, depending on the target that the surgeon must reach and the amount of working space needed to carry out a safe and successful operation. Operations that use computers and imaging such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) to guide the surgeon can use the contours of a patient’s face to serve as points of reference that can be visualized on imaging (stereotaxy).

Burr Hole

A burr hole is a small round opening in the skull that is made using a surgical drill. Creating a burr hole is usually the first step in removing a larger piece of bone in a craniotomy. However, it can be used on its own during minimally invasive procedures. Burr holes can be used to:

- Drain blood on the surface of the brain (hematoma evacuation) after a head injury for the treatment of an acute epidural or subdural hematoma

- Insert an instrument such as an endoscope to remove a tumor

- Insert a pressure monitor in the brain (intracranial pressure monitor)

- Insert a hollow tube (shunt) to drain cerebrospinal fluid and redirect it elsewhere for the treatment of hydrocephalus

- Implant electrodes into certain brain areas (deep brain stimulation) to produce electrical impulses for the treatment of movement disorders such as essential tremor or Parkinson’s disease

- Obtain a sample of tissue cells to further characterize a mass (needle biopsy)

Craniotomy

Unlike surgery on the abdomen, surgery on the brain first requires the removal of bone to access the operation site. Thus, a craniotomy is usually the first step of brain surgery. Craniotomies can be performed to reach a brain tumor, clip or repair an aneurysm, remove an arteriovenous malformation, drain a pus-filled pocket (abscess) within the brain, and more.

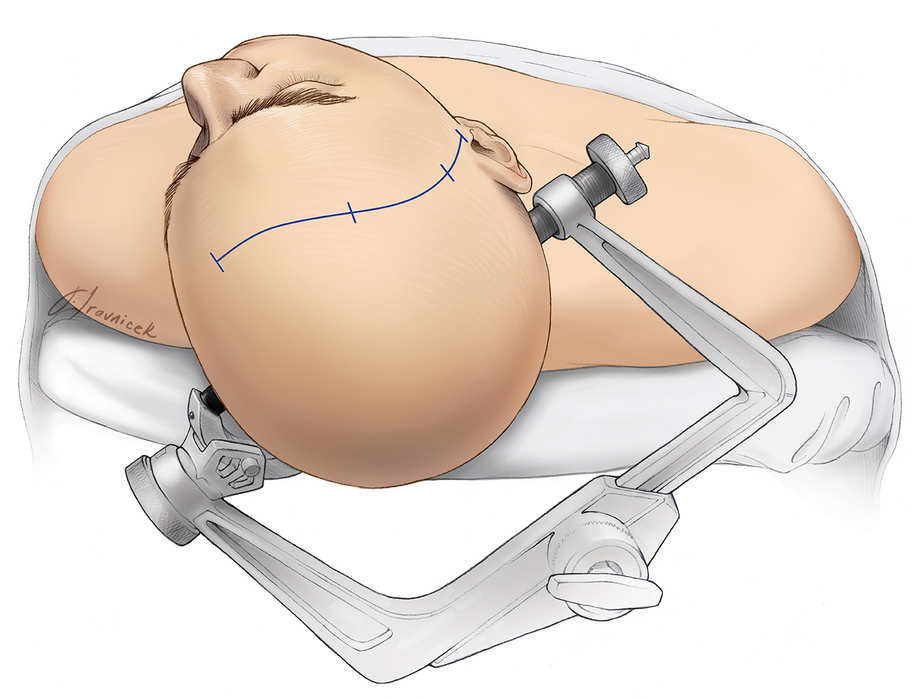

Craniotomies are named on the basis of their location and corresponding bones or anatomic landmarks. The exact location of the skin incision and how much bone will be removed should be discussed with your neurosurgeon.

Awake Craniotomy

In an awake craniotomy, the patient is woken up during one part of the brain surgery. The term “awake craniotomy” is slightly misleading, because the patient is still under some sedation when the craniotomy is being performed (bone flap is removed). When the surgeon begins operating near areas that are critical for speech, the patient is awakened to help the surgeon map which areas should be preserved to maintain normal speech function. This can be done by simply having a conversation with the neurosurgeon and anesthesiologist while the surgery is taking place. This is not a very painful procedure, because brain tissue itself cannot feel pain.

Figure 2. Craniotomies are named on the basis of their corresponding bones or anatomical landmarks. Incision lines are drawn. From top to bottom and left to right, the craniotomies are named as pterional (or frontotemporal), parietal, supraorbital, subtemporal, occipital, parasagittal, interhemispheric, and bifrontal.

Decompressive Craniectomy

An even larger piece of bone can be removed to relieve pressure on the brain. Unlike a craniotomy, a craniectomy does not reattach the bone immediately after the procedure. The bone flap is kept clean and frozen for future use when repairing the bone (cranioplasty), usually 6 weeks after the craniectomy.

As with a craniotomy, there are different types of craniectomies, depending on the level of decompression needed. However, the incision for a decompressive craniectomy is generally larger than that of a craniotomy.

Figure 3. Decompressive craniectomies are generally larger than craniotomies. The green line represents an appropriately large incision to relieve pressure on the brain, whereas an incision on the red line would be too restrictive.

Who Performs a Craniotomy?

A craniotomy is performed by a neurosurgeon, who might work with a team of otolaryngologists, plastic and reconstructive surgeons, anesthesiologists, critical care experts, interventional radiologists, oncologists, and rehabilitation experts, depending on the underlying condition being treated.

What Is a Craniotomy Performed For?

The indications for a craniotomy are diverse and depend on the type and severity of the condition being treated. Below are the primary reasons this type of brain surgery may become necessary.

Treating Brain Tumors

Brain tumors, whether benign (non-cancerous) or malignant (cancerous) can increase intracranial pressure and cause damage to the brain. A craniotomy allows surgeons to remove the tumor or, in some cases, take a biopsy to determine the nature of the growth.

Alleviating Hemorrhagic Strokes

Strokes caused by bleeding in the brain require immediate attention to prevent extensive damage. The procedure can relieve intracranial pressure due to a hemorrhagic stroke by allowing the evacuation of blood and repair of the damaged vessels.

Resolving Blood Clots

Blood clots or hematomas forming after trauma or stroke can be life-threatening and often require a craniotomy to be removed. This procedure can help restore normal blood flow and brain function.

Addressing Brain Aneurysms

A craniotomy can be necessary to treat brain aneurysms by clipping them off from the blood circulation, preventing rupture or re-bleeding. In some cases, unruptured aneurysms are surgically addressed proactively to avoid the risk of potential life-threatening hemorrhages.

Controlling Seizures

For some patients with drug-resistant epilepsy, a craniotomy allows surgeons to resect the area of the brain where seizures originate. A craniotomy can reduce or eliminate the frequency and intensity of seizures, greatly enhancing the patient’s quality of life.

What Happens Before a Craniotomy?

Before a craniotomy, the surgeon will explain what the procedure will involve and its risks and benefits. Consent forms and other paperwork will be completed to inform the surgeon of relevant medical history such as allergies, other medications you are taking, reactions to anesthesia, and any previous surgeries.

One week before surgery, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen (for example, Advil or Motrin), naproxen (for example, Aleve), and other prescribed NSAIDs, as well as blood thinners such as warfarin (for example, Jantoven, Coumadin), acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin), and clopidogrel (for example, Plavix) should be stopped to decrease the risk of bleeding. This list is not all-inclusive. Inform your physician of all medications and supplements you are taking, and follow his or her recommendations.

Several days before surgery, a physical exam, blood tests, an electrocardiogram (ECG), chest X-rays, and other tests might be performed to ensure that your body can safely undergo anesthesia and handle the surgery and that surgical scenarios (for example, bleeding) are properly prepared for. A baseline neurological exam is conducted and repeated after surgery. MRI might be scheduled if the surgeon plans to use image guidance during the operation.

On the night before or morning of the surgery, your physician might ask that you fast (not eat or drink anything) to prevent vomiting while under general anesthesia. To reduce the possibility of infection at the site of incision, showering or washing your hair with a special antiseptic shampoo might be required.

What Happens During a Craniotomy?

A craniotomy can take 1 to 2 hours to perform, and then it takes an additional 3 to 5 hours or longer for the actual treatment procedure (for example, brain tumor removal), depending on your underlying condition.

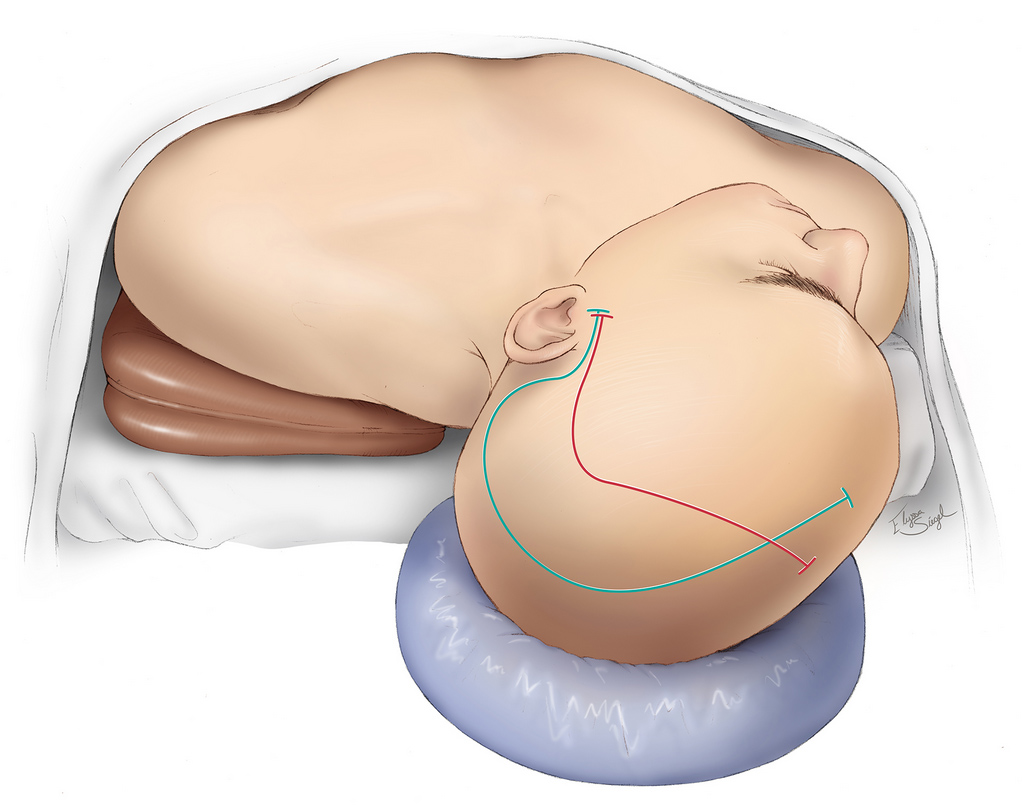

Step 1: Patient Preparation

The patient is placed on the operating table and given general anesthesia. After the patient is asleep, a breathing tube is placed into the windpipe (trachea) and connected to a ventilator that mechanically pumps oxygen to the lungs during the operation. A 3-pin skull clamp is connected to the table and the patient’s head to immobilize the head during the procedure. The patient’s hair is shaved or clipped in the area of the craniotomy. As an alternative, a hair-sparing technique might be used, which involves shaving only a ¼-inch-wide area around the planned incision line. A line is drawn on the scalp to mark the path of the initial incision.

Figure 4. While under general anesthesia, the patient’s head is positioned and immobilized with a 3-pin skull clamp.

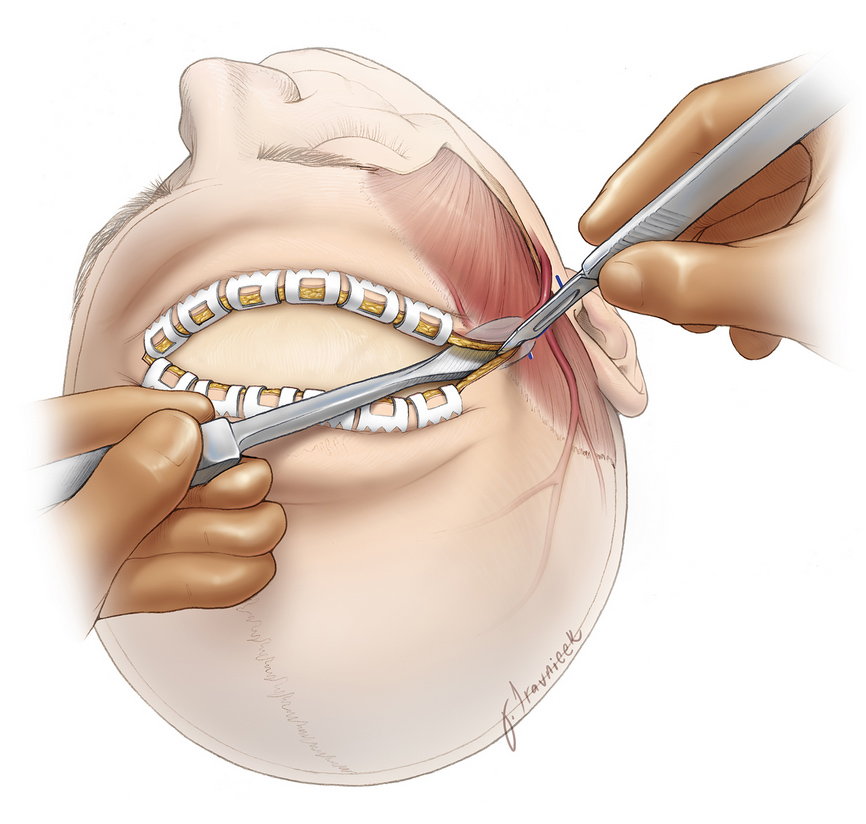

Step 2: Skin Incision

The skin around the incision line is scrubbed with an antiseptic to reduce the possibility of infection. A skin incision is made through the scalp to the outer surface of the bone/skull. Clips are applied to the edges of the cut to minimize bleeding.

Figure 5. The scalp is cut, and clips are placed on the edges to minimize bleeding. As the incision approaches muscle, a blunt tool is inserted over the muscle to protect any arteries.

Step 3: Craniotomy

Muscles, if present, are flapped back and secured. A small opening in the skull (burr hole) is made with a surgical drill called a perforator. A blunt-ended tool is inserted into the burr hole and used to separate the outer covering of the brain (dura) away from the inner part of the skull bone. Another instrument called a craniotome is then used to saw through the bone from the initial burr hole to create a removable bone flap.

Figure 6. (Left) A blunt dissector is placed through the burr hole and swept under the bone to separate the dura from the bone. (Right) A craniotome with a footplate is used to saw through the bone and create the bone flap.

Step 4: Brain Exposure and Surgery

The dura is cut open and flapped back. It might be temporarily secured to the muscle with stitches. The surgeon can then use a variety of tools (such as scissors, dissectors, ultrasonic aspirators, etc) to operate on the brain and treat the underlying condition (for example, remove a brain tumor).

Step 5: Closure

After the operation within the brain is complete, the dura is stitched back together. The bone flap is reattached using small metal/titanium plates and screws, which will remain there permanently and can sometimes be felt under the skin. Muscles and connective tissues are reaffixed/sutured to their original position. Finally, the clips are taken off of the scalp, and the edges are stitched.

Figure 8: The dura (left), bone flap (middle), and muscle and connective tissues (right) are reattached with stitches (for tissue) and metal plates (for bone).

In this video, Dr. Cohen describes the techniques for performance of a temporal craniotomy.

For more information about the technical aspects of the surgery and extensive experience of Dr. Cohen, please refer to the chapter on Temporal/Subtemporal Craniotomy in the Neurosurgical Atlas.

What Happens After a Craniotomy?

Immediately after a craniotomy, you are taken to a recovery room for monitoring as the anesthesia wears off. The breathing tube is removed (extubation), and your vital signs will be monitored. Once you are fully awake, you are taken to the intensive care unit (ICU) for further monitoring and care, including control of blood and intracranial pressures, nutrition, temperature, oxygen levels, and pain. A neurological exam is conducted periodically to check for signs of early complications, such as impaired consciousness, seizure, stroke, or intracranial bleeding.

Most patients experience pain after brain surgery. Such pain is controlled with medications such as narcotics (for example, morphine, fentanyl, or hydromorphone), acetaminophen (Tylenol), muscle relaxants (for example, methocarbamol, diazepam, tizanidine), or steroids (for example, dexamethasone). High blood pressure, nausea, vomiting, and/or shivering might occur and can be addressed with medications and blankets or air-warming devices.

After a few days or once your condition has stabilized, you are transferred to the regular hospital ward. Oxygen might be required for a period of time. The medical staff will teach you deep-breathing exercises to prevent infection of the lungs (pneumonia). Getting out of bed and walking as tolerated is encouraged, and a physical therapist might be asked to work with you. Depending on the complexity of the operation, the total hospital stay might range from a few days to weeks.

At home, you should follow the instructions provided by your surgeon. A follow-up appointment might be made in the next 1 to 2 weeks after discharge. During recovery, you might have issues with walking, talking, strength, and balance. Headaches that are described as pulsating or pounding are common and can persist for several months after surgery. In general, avoid high-intensity activities, keep the incision site clean, and take pain medicine as directed. Discuss when you can return to work with your physician. You might not be able to return to work for several weeks.

Activities

- Avoid strenuous activity (for example, lifting heavy items, jogging, sex)

- Avoid risky activities that require your attention (for example, driving)

- Do not drink alcohol or use nicotine products (for example, smoking, vaping)

- Try to walk 5 to 10 minutes per day, and gradually increase this time as you recover

- Sleep with your head elevated and apply ice 3 times per day for 15 minutes to reduce pain and swelling, if needed

- Drink water and eat foods high in fiber (for example, beans, whole grains, nuts, berries) to resolve constipation caused by the narcotics used for pain control during or after surgery

- Discuss activities such as returning to work or air travel with your physician

Incision Care

- Shower as early as 2 days after surgery

- Gently wash the incision site with soap and water daily

- Avoid hair styling products, lotions, and baths

Medications

- Take acetaminophen (Tylenol) for headaches and other pain medications as directed by your physician

- Do not take NSAIDs (for example, Advil, Aleve), blood thinners (for example, aspirin, Coumadin), or other supplements without your surgeon’s approval

When to Call Your Doctor

- Fever or chills

- Redness, swelling, bleeding, increased pain around the incision site

- Swelling at the incision site with clear fluid leaking from your ears or nose

- Excessive sleepiness, confusion, increased headaches, weakness in your arms or legs

- Vision, speech, or breathing problems

- Green, yellow, or blood-tinged sputum (phlegm)

- Seizures

Risks of a Craniotomy: What Are the Possible Complications?

Intraoperative risks and complications include the following:

- Anesthesia-related complications - Complications from general anesthesia include allergic reactions, breathing difficulties, and in rare cases, anesthesia awareness.

- Bleeding and hemorrhage - Intraoperative bleeding is a significant risk during a craniotomy and can lead to hemorrhagic stroke or require blood transfusion.

Immediate post-operative side effects may include:

- Nausea and vomiting

- Pain at the craniotomy site

- Swelling and bruising of the face

- Seizures - The irritation of brain tissue during surgery can predispose patients to post-operative seizures.

- Neurological deficits - Temporary or permanent changes in vision, balance, coordination, strength or cognitive functions might result from the surgery.

- Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks - These leaks can occur where the skull bone was removed/replaced, potentially leading to wound infection, headaches, or meningitis.

A dent where the bone flap was removed might also be present. If the craniotomy was performed near the temples, the temporalis muscle (which helps with chewing) might be cut. After the operation, the muscle on the side of the craniotomy might be slightly shortened and cause a feeling of jaw stiffness. This problem usually resolves within a few months.

Rarely, a blood clot forms near the site of the craniotomy. If large, such a clot can be removed with another operation.

What Is the Recovery Outlook?

After a craniotomy, the bone flap will mend itself over time and partially heal back into the rest of the skull bone within 2 to 3 months. Full recovery can take a few months and depends on the underlying condition that was treated.

Glossary

Bone flap—section of bone temporarily removed during a craniotomy

Burr hole—small opening through the skull made by a surgical drill

Cerebrospinal fluid—clear fluid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord

Craniectomy—procedure that removes a piece of bone from the skull to expose the brain; the bone is reattached to its original location at a later time (during a separate surgery)

Cranioplasty—surgery to repair or correct the skull bone

Craniotome—special neurosurgical saw that enables a surgeon to cut through the bone without cutting the dura mater

Craniotomy—procedure that removes a piece of bone from the skull to expose the brain; the bone is reattached to its original location immediately after the rest of the surgery

Dura mater—outermost covering of the brain

Image-guided surgery—surgery using the patient’s CT or MRI scans to guide the surgeon during the operation

Pneumonia—infection of the lungs

Seizure—sudden burst of abnormal electrical activity in the brain that leads to uncontrollable spasms, twitching, or jerking

Shunt—hollow tube used to drain cerebrospinal fluid from one place to another

Stereotactic surgery—surgery that uses the help of 3-dimensional coordinate systems to identify and perform actions on a specific target within the body

Contributor: Gina Watanabe BS

References

- De Gray LC, Matta BF. Acute and chronic pain following craniotomy: a review. Anaesthesia 2005;60:693–704. doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2044.2005.03997.x.

- Rao D, Le RT, Fiester P, et al. An illustrative review of common modern craniotomies. J Clin Imaging Sci 2020;10:81. doi.org/10.25259/JCIS_176_2020.