Traumatic Brain Injury: What the Patient Needs to Know

Overview

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is brain damage caused by an external force such as a blow or jolt to the head. Symptoms include headache, nausea and vomiting, dizziness, and loss of consciousness, but can vary widely depending on the severity of injury.

Treatment options include intensive care in the ICU, medications, and surgery. Recovery can take up to 3 months for mild and 1 – 2 years for moderate to severe injuries. Occupational therapists, physical therapists, speech language pathologists, psychologists, and vocational counselors can help patients on their road to recovery.

What Is Traumatic Brain Injury?

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is brain damage caused by an external force such as a blow or jolt to the head. TBI can occur in situations such as a fall, motor vehicle accident, contact sports, and assault. There are many ways for the brain to incur damage after trauma. We list possible conditions that can occur after TBI below.

Skull Fracture

Upon strong collision with a hard object, the skull bone can fracture just like any other bone.

- Open fracture: The bone is broken and exposed through the skin. This type of fracture is more prone to infection and is often surgically treated or explored to check the extent of deeper damage to the outer covering of the brain (dura).

- Closed fracture: The bone is broken but the skin is still intact. In cases where there is no significant underlying collection of blood, this may heal over time without treatment.

Why should you have your surgery with Dr. Cohen?

Dr. Cohen

- 7,500+ specialized surgeries performed by your chosen surgeon

- More personalized care

- Extensive experience = higher success rate and quicker recovery times

Major Health Centers

- No control over choosing the surgeon caring for you

- One-size-fits-all care

- Less specialization

For more reasons, please click here.

Figure 1: A skull fracture is illustrated (left). Bone fragments are removed and blood is evacuated using a suction (middle). Following cleanup, bone fragments are replaced and screwed back on to the skull bone (right).

Bruising of the Brain (Cerebral Contusion)

The brain is cushioned within the skull by the presence of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Sudden impact to the outside of the skull may cause the brain to collide with the inner walls of the skull and bruise.

- Coup injury: Brain injury at the site of impact. This occurs due to force transmission from the site of impact to the underlying brain tissues.

- Contrecoup injury: Brain injury on the opposite side of impact. This is due to collision of the brain on the bony inner walls of the skull on the opposite side of the impact site.

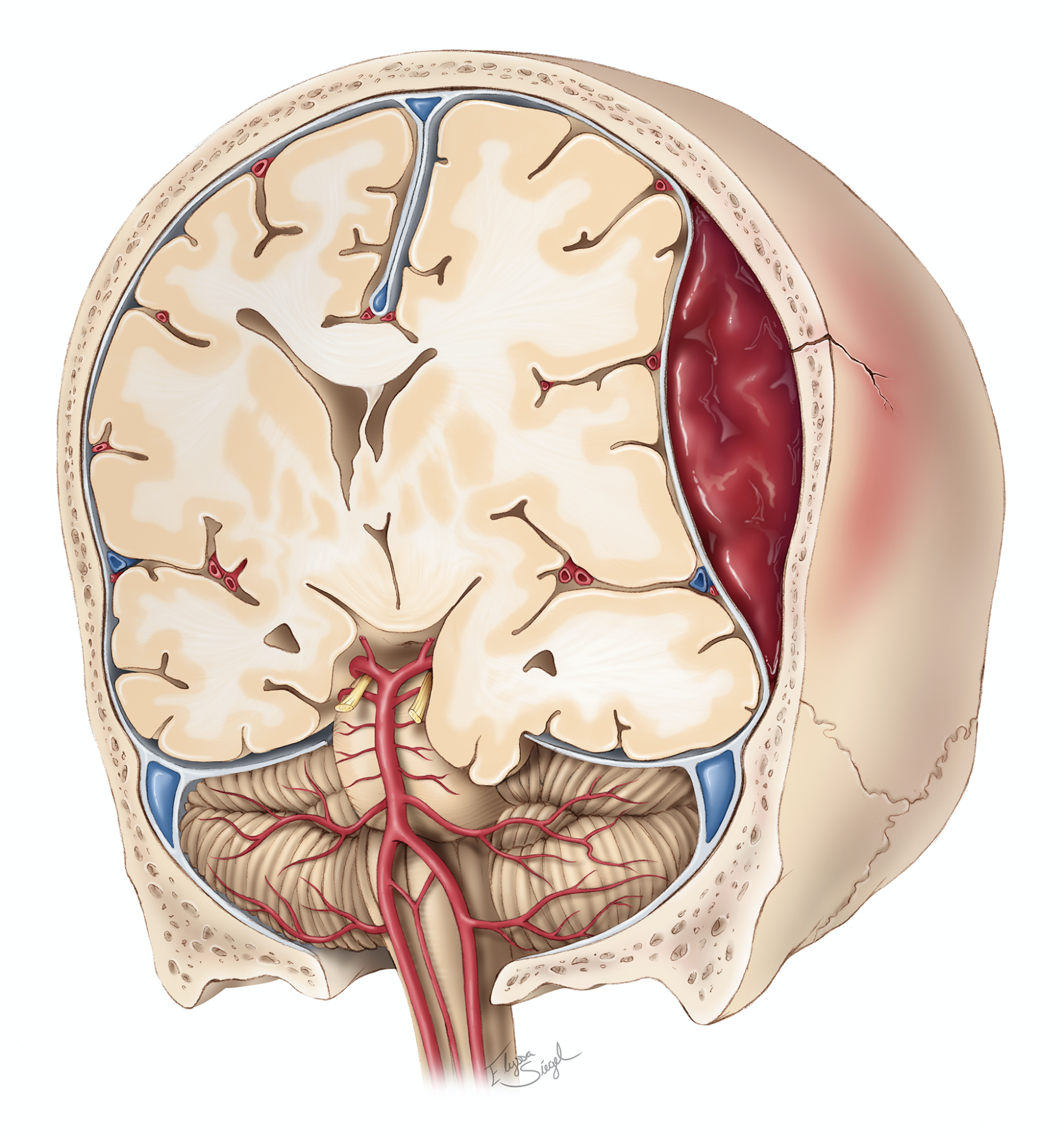

Bleeding

A strong blow to the head can cause blood vessels to rupture and bleed. Blood can pool outside of the brain but remain within the skull. We can classify this based on where the bleeding occurs.

- Epidural hematoma: Bleeding occurs above (epi-) the outermost covering of the brain (dura) but remains within the skull bone. This is usually caused by a blunt force trauma that tears the middle meningeal artery.

- Subdural hematoma: Bleeding occurs below (sub-) the dura, specifically between the dura and the arachnoid mater layers of the meninges. This is usually caused by rupture of the bridging veins. Since the pressure of blood flowing in veins is lower than that of arteries, a venous bleed can be slow and not cause symptoms until days, weeks, or months after the initial trauma.

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage: Bleeding occurs below (sub-) the arachnoid mater and into the subarachnoid space. This is also where cerebrospinal fluid exists to cushion the surrounding brain and spinal cord.

Figure 2: A large epidural hematoma is formed after blunt injury to the skull. This expanding collection of blood will push the brain towards the other side and can damage critical brain structures.

An enlarging collection of blood may compress the brain to the point where it herniates across rigid connective tissues (for example, the falx, or tentorium cerebelli) or through natural openings of bone (for example, foramen magnum).

Diffuse Microscopic Injury

In a motor vehicle crash or other situations where high-speed acceleration is followed immediately by rapid deceleration, the entire brain lags behind as the head jerks forward.

This produces microscopic tears throughout the brain and often results in severe neurological injury even though images of the brain may appear relatively normal (diffuse axonal injury).

What Are the Symptoms?

TBI can be categorized by severity with general symptoms as follows. However, head trauma should be taken very seriously, even if a person appears normal after a fall or other blow to the head and only briefly loses consciousness. Loss of consciousness is an important factor for thorough evaluation.

If bleeding occurs in the brain after a TBI, the amount of bleed leaking from the blood vessel may not be large enough to cause symptoms. After briefly losing consciousness, a person may appear normal for a period of time (lucid interval). Throughout the day, bleeding continues and forms a large collection of blood that can compress the brain and cause neurological deficits.

By the time medical attention is sought, severe and permanent neurological damage may occur. In the worst case, symptoms go unnoticed until the person falls asleep where bleeding continues untreated and causes death. Seek medical attention for any significant head trauma early!

Mild TBI

- Headache

- Nausea and vomiting

- Fatigue

- Trouble with speech

- Dizziness

- Loss of coordination

- Changes in vision

- Ringing in the ears (tinnitus)

- Loss of smell

- Brief loss of consciousness

- State of disorientation

- Changes in memory

- Difficulty concentrating

- Mood swings

- Trouble sleeping or sleeping excessively

Moderate to Severe TBI

- Prolonged loss of consciousness

- Worsening headache

- Unrelenting vomiting with nausea

- Seizures

- Weakness or numbness in extremities

- Loss of coordination

- Confusion

- Agitation

- Slurred speech

- Coma

What Are the Causes?

TBI is caused by an external force such as a blow or jolt to the head and can occur due to falling from significant heights, motor vehicle collisions, violence (ex: gunshot, domestic violence, abuse, or assault), sports injuries, and explosions or combat. Falls, being struck by or against an object, and motor vehicle accidents are among the most common causes.

How Common Is It?

TBI is common with 64 to 74 million new cases of TBI occurring each year globally. In the United States, approximately 800 to 1300 per 100,000 people sustain a TBI. These numbers are likely underestimates as patients with mild TBI may not seek medical attention. TBI occurs more frequently among young children (0 – 4 years old), adolescents (15 – 19 years old), and older adults (≥ 75 years old).

How Is It Diagnosed?

TBI is diagnosed by obtaining a history of the traumatic event if possible, performing a neurologic exam to determine what parts of the brain may be affected, and ordering imaging:

CT scan—this imaging technique uses a series of X-rays to create an image of the brain’s structures. These are used to detect skull fractures, and bleeding or blood clots in the brain.

MRI scan—this imaging technique uses radio waves and magnets to create an image of the brain’s structures. This technique avoids exposure to radiation and provides higher detail of brain tissues than a CT scan but takes more time to create an image. For this reason, MRIs often are not done until the individual is in a stable condition or after treatment to check if the treatment was successful.

What Are the Treatment Options?

Treatment of TBI depends on the severity of the initial injury. For mild injuries, watchful rest is most important. For severe or life-threatening TBIs, patients may require care and monitoring in the intensive care unit.

Neurocritical Care

Patients suffering from a severe TBI may require monitoring and treatment in the neurological intensive care unit (ICU). In many cases of severe brain injury, patients are unconscious, paralyzed, and have difficulty performing normal functions such as breathing, eating, and urinating.

In the ICU, patients are connected to monitoring equipment and other machines to temporarily take over these functions until the patient recovers.

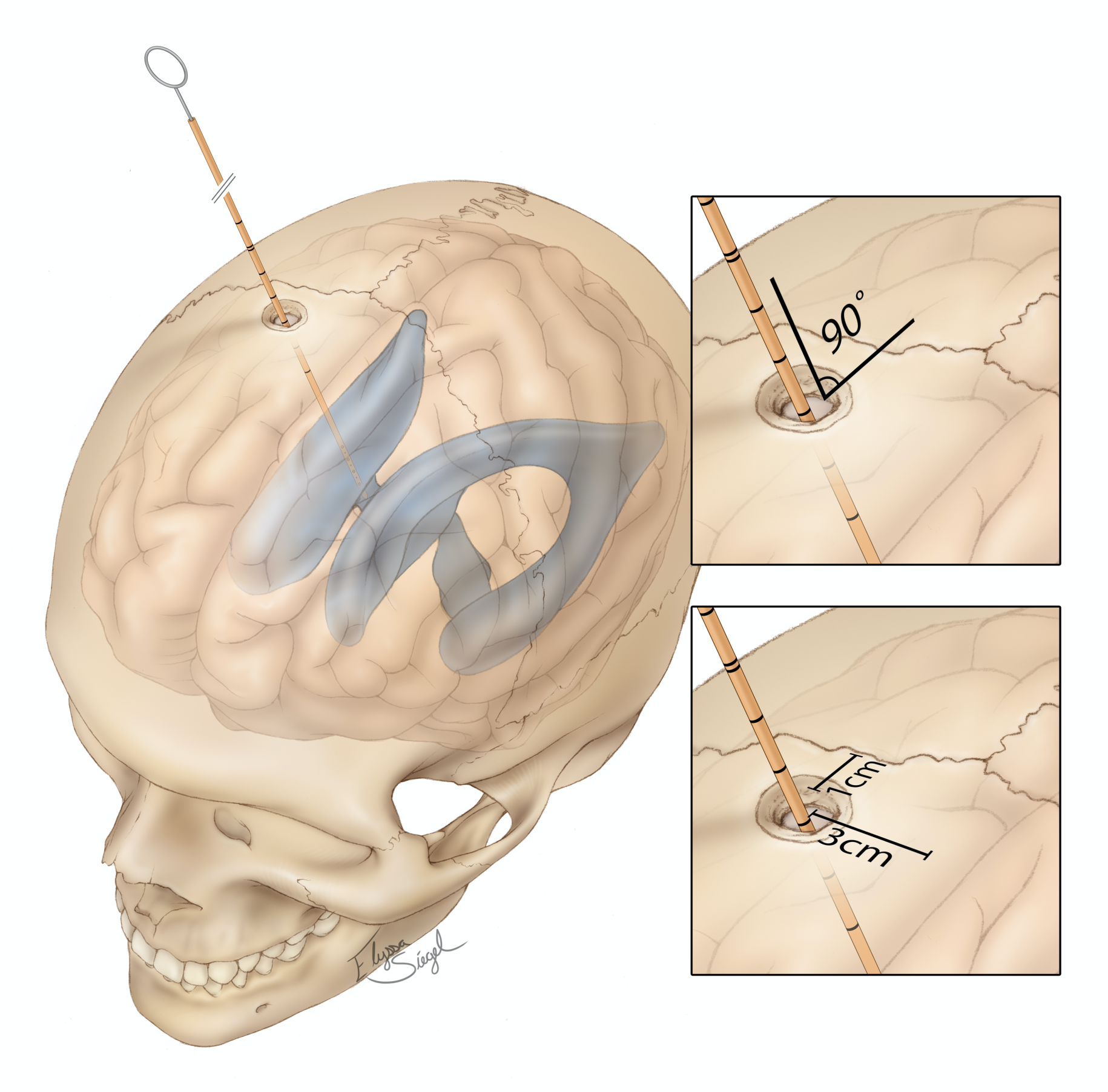

Intracranial Pressure—Buildup of blood or swelling of the brain can lead to increased intracranial pressure (ICP) and decreases the pressure gradient required for delivery of oxygenated blood to the brain.

An ICP monitor is placed by creating a small hole in the skull and inserting a catheter into a cavity of the brain (ventricle) to measure pressures within the head. If ICP becomes too high (typically > 20 mmHg), the team can swiftly act to reduce pressure through medications or surgical procedures.

Elevating the head can also help to reduce ICP. In cases of acute neurological deterioration, making the patient take more rapid breaths (hyperventilation) may also be used to lower ICP.

Brain Oxygen—The amount of oxygen present within brain tissues can be measured with a brain oxygen monitor (for example, Licox). If the level of brain oxygen is too low, the team can increase the amount of oxygen given to the patient. Blood flow monitors may also be used.

Breathing—Some patients require mechanical pumping of oxygen into the body with a ventilator. To set up mechanical ventilation, an endotracheal tube is first inserted through the patient’s nose or mouth and guided downwards into the windpipe (trachea). The tube is then connected to a ventilator that can push oxygen into the lungs.

Nutrition—Patients that are on a ventilator, have difficulty swallowing, or who are unable to feed themselves may require a feeding tube. Nasogastric tubes are inserted into the nose and down through the throat. The cap on the top of the tube can be opened to administer food and fluids.

Seizure Prevention—In patients with moderate to severe TBI, seizures can occur in approximately 1 in 5 patients during the first week after injury. An electroencephalogram (EEG) monitors electrical activity of the brain and can detect seizures.

If abnormal electrical activity is noted, physicians can monitor the patient more closely and swiftly intervene if a seizure occurs. Providing antiseizure medications may also help to prevent seizures from even occurring.

Medications

Medications to relieve pain, control intracranial pressure, prevent seizures and prevent infection may be administered. In cases where brain swelling is significant and does not resolve after other treatments, a medically induced coma may be indicated.

In this procedure, the physician infuses an anesthetic to produce a controlled state of unconsciousness. This allows the brain to relax, significantly decreases its metabolic demand, and lowers ICP.

Surgery

Surgery may be needed to repair a skull fracture, mend bleeding blood vessels, remove large blood clots (hematoma), drain excess cerebrospinal fluid from the brain, or relieve high intracranial pressure. The following are possible surgical procedures for TBI.

- Craniotomy—To access the brain, surgeons must make a small hole within the bony skull encasing the brain (cranium). A craniotomy simply refers to removal of a part of the cranium and is often the first step before any neurosurgical procedure that requires access to the brain.

Figure 3: Craniotomy is performed by using a special saw called a craniotome to cut through the bone (left) and this bone flap is temporarily removed to access the brain during surgery (right).

- Decompressive Craniectomy—A decompressive craniectomy removes a larger piece of bone than a craniotomy to relieve pressure on the brain. Unlike a craniotomy, a craniectomy does not reattach the bone immediately after the procedure. The bone flap is kept clean and frozen for future use when repairing the bone.

Figure 4: Decompressive craniectomies are generally larger than craniotomies. The green line represents an appropriately large incision to relieve pressure on the brain, whereas an incision on the red line would be too restrictive.

- Ventriculostomy—To setup ICP monitoring, a thin catheter must be inserted into ventricles of the brain. This involves creating a small hole in the skull.

Figure 5: Placement of the catheter into a ventricle of the brain.

What Is the Recovery Outlook?

In mild TBI cases, complete recovery may take up to 3 months or longer depending on the patient’s age and other health conditions. Most recovery takes place within the first two years.

In moderate and severe TBI cases, approximately 50% and 75% of patients recover functional independence at home by the first year after injury. Occupational therapists, physical therapists, speech language pathologists, psychologists, and vocational counselors can help patients on their road to recovery.

Resources

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

Brain Injury Association of America

Kessler Foundation Center for Traumatic Brain Injury Research

Glossary

Catheter—thin, hollow and flexible tube

Cerebrospinal fluid—clear fluid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord

Cranium—fixed space in the head that contains the brain

Hemorrhage—bleeding from a blood vessel

Hydrocephalus—accumulation of fluid within the brain

Intracranial pressure—pressure within the cranium

Subarachnoid space—space beneath the arachnoid membrane that consists of cerebrospinal fluid and blood vessels

Ventricles—network of cavities within the brain filled with cerebrospinal fluid

Contributors: Carolyn Scheuler, Gina Watanabe BS

References

- Faul M, Coronado V. Epidemiology of traumatic brain injury. Handb Clin Neurol. 2015;127:3-13. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-52892-6.00001-5

- Dewan MC, Rattani A, Gupta S, et al. Estimating the global incidence of traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg. Published online April 1, 2018:1-18. doi:10.3171/2017.10.JNS17352

- Capizzi A, Woo J, Verduzco-Gutierrez M. Traumatic Brain Injury: An Overview of Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Medical Management. Med Clin North Am. 2020;104(2):213-238. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2019.11.001

- Ma M, Jt G, J B, et al. Functional Outcomes Over the First Year After Moderate to Severe Traumatic Brain Injury in the Prospective, Longitudinal TRACK-TBI Study. JAMA neurology. 2021;78(8). doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.2043