Endovascular Treatment for Arteriovenous Malformation

Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) of the brain are tangles of abnormal arteries and veins lacking fine branching blood vessels called capillaries between them. This creates turbulent blood flow that can eventually cause the vessels to tear and bleed. Prevention of hemorrhage is one of the reasons why AVMs may require treatment. In this article we will discuss endovascular treatment of AVMs, including what it is, when it is indicated, and long-term outcomes.

What is Endovascular Treatment for Arteriovenous Malformation?

Endovascular means inside (“endo”) the blood vessels (“vascular). Endovascular procedures thus are minimally invasive techniques using tools that can fit within the blood vessels such as thin flexible tubes (catheters) and wires. In contrast to open surgery, the incision site is very small. Catheters can be inserted into a blood vessel at an arm or leg and threaded up to the site of the lesion in the brain. Once the desired location is reached, contrast agents or medical glue can be administered to diagnose and treat AVMs, respectively.

There are several endovascular procedures that you may encounter in the management of an AVM. During initial diagnostic workup or evaluation of an AVM, an imaging test called an angiogram is typically ordered. For treatment of an AVM, endovascular embolization may be recommended as an adjunct to surgery, or in rare cases, as primary treatment. These two procedures are described in more detail below.

Angiography

Angiography is an endovascular procedure that involves inserting a catheter into a blood vessel either in the crease of the groin or wrist, then advancing it up into the blood vessels of the brain. Contrast dye is then injected through the catheter and x-ray images are taken. This imaging test provides essential information to the surgeon by displaying the size, location, and structure of the AVM and its nearby blood vessels.

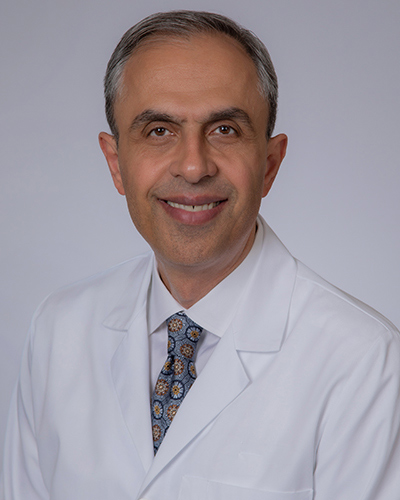

Why should you have your surgery with Dr. Cohen?

Dr. Cohen

- 7,500+ specialized surgeries performed by your chosen surgeon

- More personalized care

- Extensive experience = higher success rate and quicker recovery times

Major Health Centers

- No control over choosing the surgeon caring for you

- One-size-fits-all care

- Less specialization

For more reasons, please click here.

Endovascular Embolization for AVN

Like angiography, endovascular endovascular embolization for AVMinvolves inserting a catheter into a blood vessel in the arm or leg and advancing it up into the blood vessels of the brain. However, instead of injecting a contrast dye, a special type of “glue” is administered. The catheter is guided towards a blood vessel that provides blood flow to (“feeding”) the AVM, then the liquid glue is released. Soon, the glue solidifies and prevents blood from passing through, thereby blocking blood flow to the AVM. This procedure is especially helpful to occlude deep feeding arteries that are difficult to surgically reach.

If endovascular embolization for AVM is part of the treatment plan, it is typically used in combination with surgical removal of the AVM, with embolization being performed prior to surgery. Preoperative embolization may help to shrink the size of the AVM, facilitating an easier and safer surgical operation. In rare cases, endovascular embolization alone can cure an AVM. This is more possible with small AVMs involving only a single direct feeding blood vessel.

In palliative embolization, the goal of the procedure is to eliminate the largest abnormal blood vessel in the AVM to improve symptoms. This may be performed in patients who are experiencing severe headaches, seizures, and other neurological symptoms that are thought to be caused by the AVM, but other treatment options such as surgery are deemed too risky.

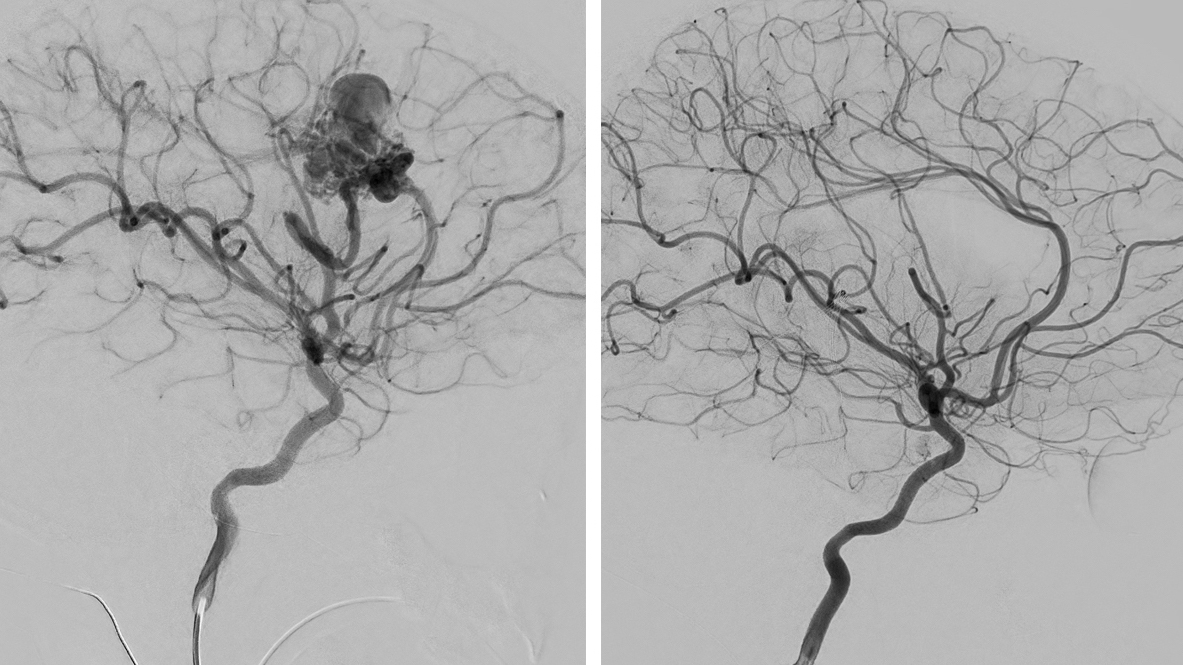

Figure 1: Large AVM before (left) and after (right) endovascular embolization and surgical removal.

There are many different types of embolic agents available. The most common types are as follows:

- N-butyl cyanoacrylate (NBCA): An adhesive liquid agent also referred to as glue that quickly becomes solid when in contact with blood. This leads to permanent blockage of the blood vessel. The glue can stick to the catheter making it difficult to remove after embolization.

- Ethylene-vinyl alcohol copolymer (Onyx): A non-adhesive liquid agent that also solidifies in blood. The solution is mixed with contrast material to provide visibility on x-rays so that a surgeon can quickly check the degree of blood vessel blockage in between infusions. The viscosity of the agent can also be changed, with less concentrated mixtures being able to penetrate farther into a blood vessel. Since it is non-adhesive, it does not stick to the catheter and allows for easier catheter removal after embolization.

- Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA): Special particles available in different sizes that promote clotting when administered into small blood vessels. Blood is blocked off more slowly than other liquid agents such as glue or Onyx. PVA embolization is often temporary so is typically done in preparation for surgery.

What Can I Expect Before and After the Procedure?

The length of endovascular embolization for AVM procedures varies but can take several hours. In some instances, endovascular embolization may be performed in stages over several sessions. This is dependent on the structure and size of the AVM and is individualized for each patient.

Patients may be placed under general anesthesia or receive sedatives for comfort during the catheter placement but kept awake for neurological testing. With general anesthesia, the patient is unconscious throughout the procedure and awoken afterwards. This ensures that the patient is completely still during the procedure. However, if a critical blood vessel was blocked off, there would be no way to tell until after the procedure is over.

If the patient is sedated but kept conscious, the operating team will perform a neurological exam before and after injecting a small amount of glue to test if the vessel is supplying blood to critical brain tissues. If there are no neurological deficits, the operators can continue to administer the full amount of glue. However, this approach means that the patient must be able to keep very still throughout the procedure.

Currently, there is no evidence of differences in complication rates between general anesthesia versus conscious sedation during endovascular embolization for brain AVMs. The decision to choose one over the other is based on surgeon and patient preference. After the procedure, patients are often kept overnight for monitoring of vital signs and any neurological changes.

Although less invasive than surgery, endovascular embolization does not come without risks. The most feared potential complications include rupture of the AVM during the procedure, or occlusion of blood flow to normal blood vessels causing a stroke. These complications are rare, but patients are often kept overnight for monitoring.

Long-Term Outcomes

Endovascular embolization is generally not a curative procedure. This means that most of the time, embolization is not used to cure the AVM, but to help make it easier for surgery or radiosurgery to completely remove/occlude the AVM. In certain rare cases, endovascular embolization may be curative. This is more likely in AVMs that are small and simple with only a single direct feeding vessel.

If used alone, cure rates of endovascular embolization for low-grade AVMs is low with only 20 – 30% of patients experiencing a lasting cure. In contrast, surgery can have cure rates in up to 100% of patients and thus is the primary treatment modality.

Key Takeaways

- Endovascular procedures are minimally invasive and involve guiding a catheter through a blood vessel to the AVM.

- NBCA, Onyx, and PVA particles are the most commonly used embolic agents.

- Endovascular treatment is typically used in combination with surgery or radiosurgery to treat an AVM, though in some rare cases can be used alone.