Hemifacial Spasm: What the Patient Needs to Know

Overview

Hemifacial spasm is a neurological disorder that causes a person’s facial muscles to involuntary contract. Patients with hemifacial spasm typically present with involuntary twitching on one side of the face. This twitching usually starts around the eye and spreads to other facial muscles as the disease progresses.

Patients may experience issues with their sight, hearing and speaking, and may even experience twitching while asleep. There are non-surgical treatment options to temporarily manage the symptoms of hemifacial spasms. However, surgery is the only option that can definitively cure hemifacial spasm.

What Is Hemifacial Spasm?

Hemifacial spasm is a cranial nerve hyperactivity disorder that causes involuntary contraction of the facial muscles. This condition is partially caused by compression of the facial nerve by a structure such as a blood vessel.

The facial nerve exits the brainstem, travels through the bone behind the ear, and then divides into 5 branches to provide motor activity to the face. When the facial nerve is compressed, it can become hyperactive and send signals to the facial muscles to move involuntarily, which causes twitching and spasms on one side of the face.

The condition is not usually painful but can be disruptive and stressful in social situations. It can also affect vision.

Why should you have your surgery with Dr. Cohen?

Dr. Cohen

- 7,500+ specialized surgeries performed by your chosen surgeon

- More personalized care

- Extensive experience = higher success rate and quicker recovery times

Major Health Centers

- No control over choosing the surgeon caring for you

- One-size-fits-all care

- Less specialization

For more reasons, please click here.

Figure 1: A patient suffering from hemifacial spasms.

What Are the Symptoms?

Patients with hemifacial spasms can typically present with the following symptoms:

- Involuntary twitching on one side of the face, starting around the eye

- Muscle twitching on one side of the face, particularly near the cheek and mouth

- Muscle twitching even while asleep

Although hemifacial spasms are not a disabling condition, they can affect one’s lifestyle and quality of life. Prolonged facial twitching can lead to visual impairments, which make activities such as reading and driving difficult.

Some patients complain of a “ticking” sound on the affected side, which is caused by contractions of a small muscle in the middle ear called the stapedius. Symptoms can worsen with psychological stress and speaking.

What Are the Causes?

Hemifacial spasms are thought to be caused by compression of the facial nerve (cranial nerve VII) at the level of the brainstem (by a structure such as a blood vessel or tumor), hyperactivity of the cluster of facial nerves within the brainstem, or a combination of these two conditions. These can develop through:

- A facial nerve injury

- A tumor

- Bell's palsy

In some cases, there is no apparent cause for hemifacial spasms.

How Common Is It?

Hemifacial spasm is estimated to occur in 11 per 100,000 individuals and is more common in females. The onset of symptoms is mostly during the fourth or fifth decade of life. On average, patients suffer from this condition for approximately 8 years before finding definitive treatment. This disease is unfortunately often misdiagnosed.

How Is It Diagnosed?

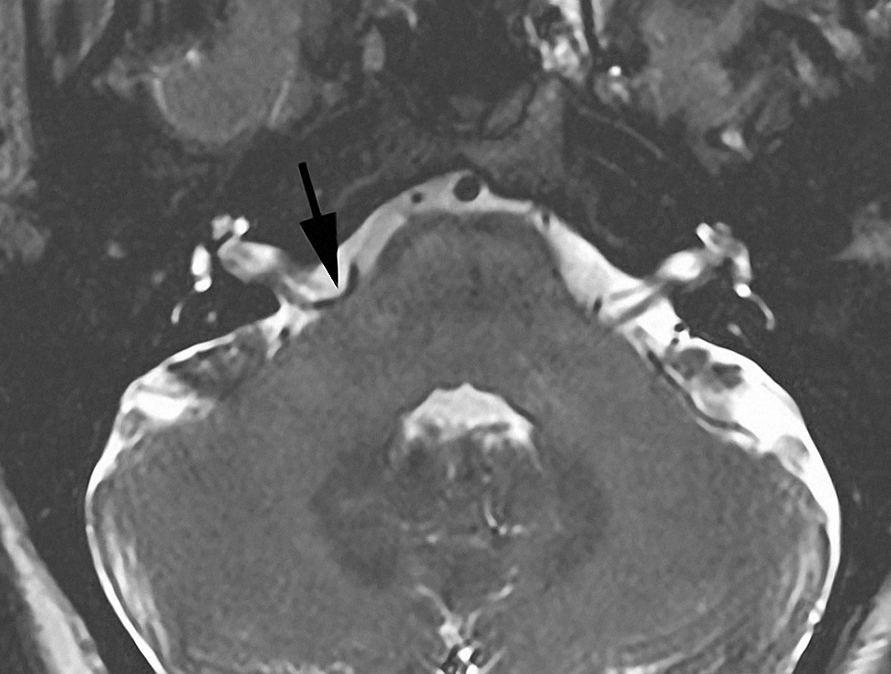

Hemifacial spasms are diagnosed clinically. No imaging or testing modality has been found to reliably diagnose this condition. Obtaining a detailed history and physical examination is critical for reaching the correct diagnosis. High-resolution magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can help to identify a blood vessel that is compressing the facial nerve. However, it is also possible for no abnormality to be found.

Figure 2: MRI demonstrating a blood vessel loop (arrow) around the root of the facial nerve.

What Are the Treatment Options?

Treatment options for hemifacial spasm include medical therapy and surgery. Botulinum toxin (Botox) injections can help reduce spasms, but it does not treat the cause of the problem. If medical therapies fail, microvascular decompression surgery can provide lasting relief in most patients.

Medications

Drugs such as carbamazepine, clonazepam, baclofen, and gabapentin have been used to treat hemifacial spasm. However, adverse effects including fatigue, exhaustion, and poor performance have been noted.

Botox is one of the most common injections used to treat spasms. The toxins reduce spasms by blocking nerve signals that cause muscle twitching. However, this is a temporary solution, as the twitching gradually returns within three to six months after the toxin wears off. Repeat treatments are necessary to maintain the effect. Risks can include nerve damage from repeated injections. These injections may injure some of the motor nerve terminals and partially explain why some patients have facial weakness after treatment despite successful relief of the spasms.

Surgery

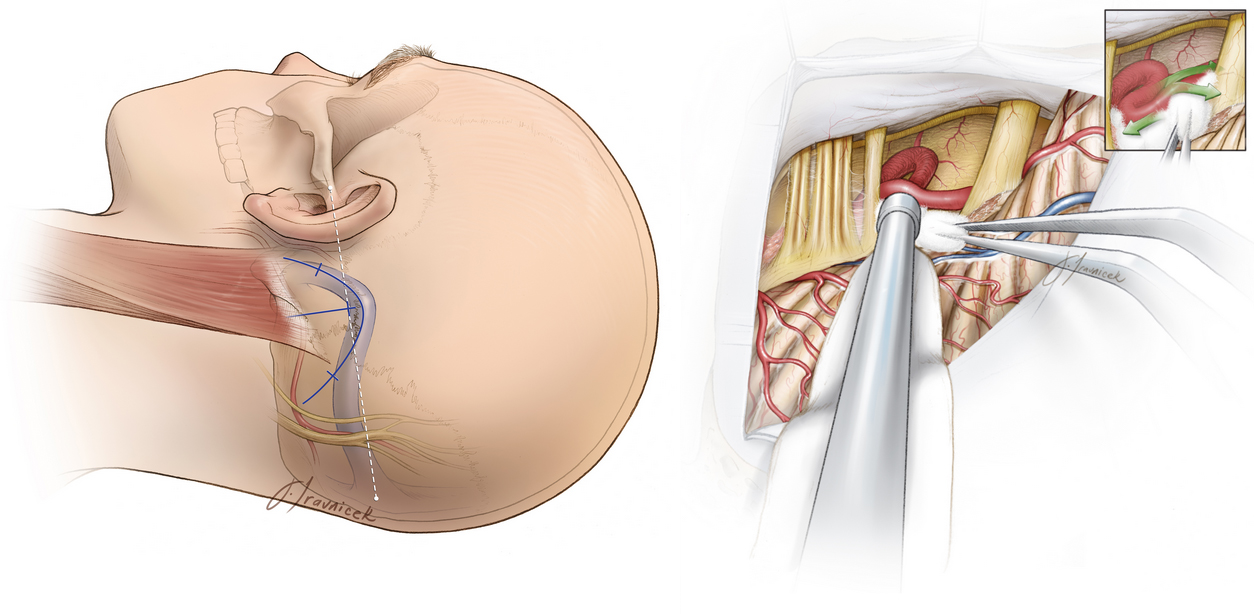

Non-surgical treatment options are often short and provide temporary relief, which is why most patients proceed with surgery for hemifacial spasms. Because it is not a disabling condition and surgery is pursued for improved cosmetic outcomes, surgery must be conducted with minimal risk to the patient. The surgeon’s experience is critical for a safe and favorable outcome.

Sometimes, hemifacial spasms go away on their own. Thus, some surgeons prefer to operate on patients with more severe symptoms that have lasted for at least 1 to 2 years. Surgery is not usually recommended for patients with hearing loss on the unaffected side because hearing loss is a possible complication of surgery, so complete hearing loss in both ears is a risk for these patients.

Figure 3: (Left) An incision path is marked behind the ears (blue line). (Right) The offending blood vessel is found compressing the facial nerve, and a cushion (Teflon implant) is placed between them to relieve the pressure.

After surgery, patients might have spasms that will resolve gradually. Delayed facial paralysis or weakness occurs occasionally, but it is temporary and responds well to medications such as dexamethasone. Other complications of surgery include:

- Infection

- Excess fluid within the cavities of the brain (hydrocephalus)

- Cerebrospinal fluid leak

- Blood loss

- Loss of function in the cranial nerves.

In this video, Dr. Cohen describes the techniques for surgery to treat hemifacial spasm.

For more information about the technical aspects of the surgery and extensive experience of Dr. Cohen, please refer to the chapter on Microvascular Decompression for Hemifacial Spasm in the Neurosurgical Atlas.

What Is the Recovery Outlook?

In 80% to 90% of appropriately selected patients, complete cure is possible with microvascular decompression surgery. The speed of spasm resolution for each person varies. Some patients might still have spasms right after surgery, but the twitching typically ceases completely over time.

Request a Consultation with a Globally Renowned Neurosurgeon

Hemifacial spasms are a rare disorder that’s often misdiagnosed or overlooked for nearly a decade before most patients can be diagnosed. Because of its rarity, there’s a risk that those with spasms are often misdiagnosed. If you are experiencing symptoms of a hemifacial spasm that is affecting your quality of life, we encourage you to schedule a second opinion with Dr. Aaron Cohen-Gadol and his team.

Aaron Cohen-Gadol, MD, is one of the most prominent neurosurgeons in the world. One of the few recipients of the Vilhelm Magnus Medal, the highest honor in neurosurgery, he has performed thousands of complex brain surgeries and delivered the best outcome for countless patients. One of his specialties includes diagnosing and treating hemifacial spasms.

Fill out our online form to schedule a second opinion.

Resources

Glossary

Spasm—sudden involuntary contraction of muscles

Contributor: Gina Watanabe BS

References

Barker FG, Jannetta PJ, Bissonette DJ, et al. Microvascular decompression for hemifacial spasm. J Neurosurg 1995;82:201–210. doi.org/10.3171/jns.1995.82.2.0201

Cohen-Gadol AA. Microvascular decompression surgery for trigeminal neuralgia and hemifacial spasm: naunces of the technique based on experiences with 100 patients and review of the literature. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2011;113:844–853. doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2011.06.003