Meningioma: What the Patient Needs to Know

Overview

A meningioma is a typically benign and slow-growing tumor that develops from the protective membranes (meninges) surrounding the brain and spinal cord.

Symptoms depend on the size and location of the tumor and include headaches, seizures, vision changes, memory loss, and balance and hearing problems.

Treatment options include surgery and/or radiation. The survival rate is usually excellent for patients with a benign meningioma in a surgically accessible location, with approximately 90% of patients surviving at 10 years.

What Is a Meningioma?

A meningioma is a tumor that develops from the protective membranes (meninges) surrounding the brain and spinal cord. These tumors push and compress rather than invade the brain. Sometimes they grow outward and cause thickening of the skull. Meningiomas are the most common type of benign brain tumor.

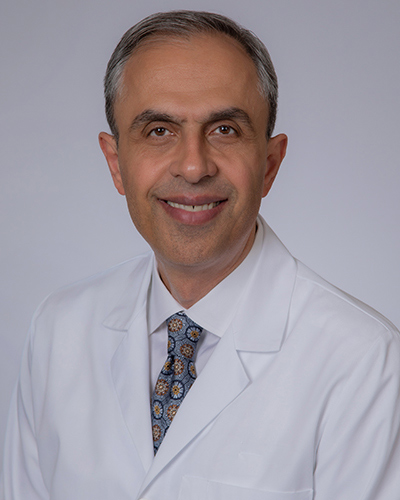

Why should you have your surgery with Dr. Cohen?

Dr. Cohen

- 7,500+ specialized surgeries performed by your chosen surgeon

- More personalized care

- Extensive experience = higher success rate and quicker recovery times

Major Health Centers

- No control over choosing the surgeon caring for you

- One-size-fits-all care

- Less specialization

For more reasons, please click here.

Figure 1. A large meningioma pressing on the brain.

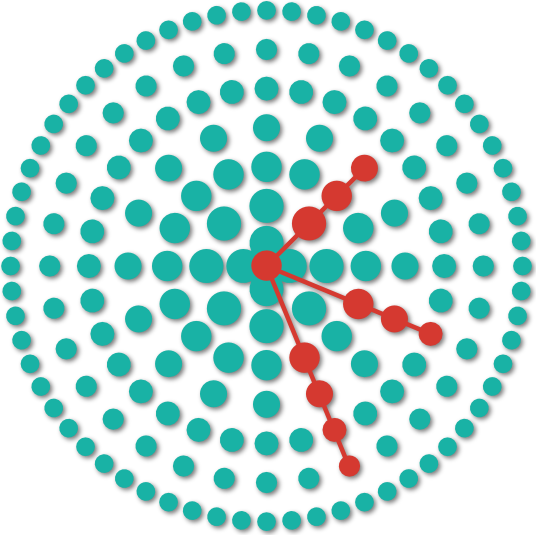

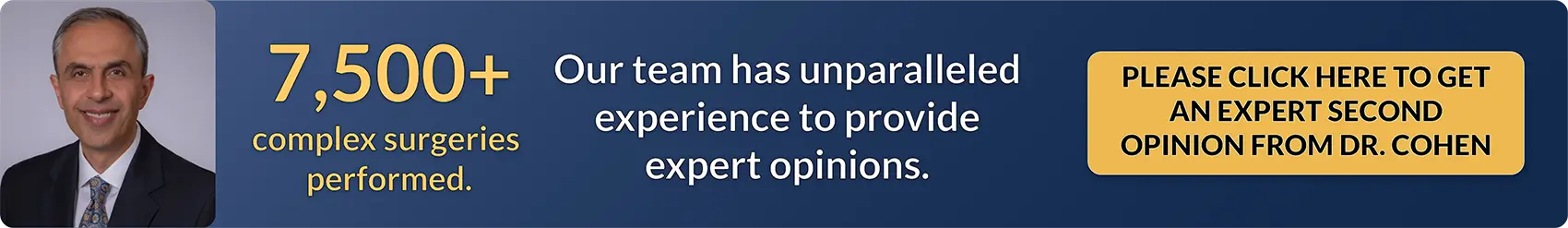

Meningioma Locations and Frequencies

Meningiomas are generally well-defined and conform to the space they inhabit. Most benign tumors do not invade normal surrounding brain tissue, and any abnormal neurological problem is generally the result of increased pressure and compression on the surrounding brain or nerves.

Figure 2. Common locations of meningiomas found around the brain.

Meningiomas are rarely cancerous. Atypical or cancerous (malignant) meningiomas possess a higher number of actively dividing cells and grow more rapidly than benign meningiomas.

In addition, they are more invasive than their benign counterparts and can project into normal brain tissue.

Malignant meningiomas can spread to other parts of the central nervous system or even the rest of the body, causing additional symptoms and making treatment more difficult.

What Are the Symptoms?

The symptoms resulting from a meningioma depend on the size, location, and rate of growth of the specific tumor. Patients with a small meningioma are often asymptomatic.

If symptoms do occur, they are usually the result of an overall increase in intracranial pressure or from the tumor compressing nearby nerves or brain tissue.

Symptoms of a meningioma can include:

- Seizures

- Progressively worsening headaches

- Problems with memory

- Balance or hearing difficulties

- Problems with eyesight

- Numbness or weakness in an arm or leg

- Confusion

- Personality changes

- Swallowing difficulties

- Hydrocephalus (build-up of brain fluid) caused by blockage of brain (cerebrospinal) fluid flow

Because meningiomas are usually very slow-growing tumors, symptoms can be subtle and evolve slowly with time. Thus, a meningioma may go undiagnosed for months or years before the patient seeks medical attention.

What Are the Causes?

Meningiomas arise from cells of the arachnoid, the middle layer of the meninges. Although gene mutations cause the development of cancer, the underlying cause of meningiomas is unknown.

Meningioma Risk Factors

Meningioma risk factors aren’t always the single cause of this condition, but they are associated with a higher likelihood of tumor development. Understanding these can help in recognizing who might be more vulnerable to meningiomas.

Genetic Disorders

Some cases may have a genetic component. For instance, individuals with Neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) have a higher risk of meningioma.

Hormonal Therapy

Some studies suggest that hormonal therapy, particularly the use of hormones like progesterone or growth hormones, may be associated with an increased risk of developing meningiomas.

Age and Gender

Meningiomas are more commonly diagnosed in older adults, with the risk increasing as age advances. The median age at diagnosis is around 66 years old. Gender also plays a role, as women are more frequently affected than men.

Exposure to Radiation

Radiation exposure, particularly high-dose ionizing radiation and especially at a young age, increases the risk of developing meningiomas.

If you’re concerned about any of these risks, it’s best to speak with your healthcare provider about your situation and possible preventive steps or screening measures.

How Common Is It?

Meningiomas are the most common benign brain or other central nervous system tumor and account for approximately 38% of such tumors.

Women are affected more commonly than men, and adults are more prone to developing meningiomas than children.

Diagnosis is most common among patients between the ages of 40 and 70 years, and less than 2% of reported cases occur in children.

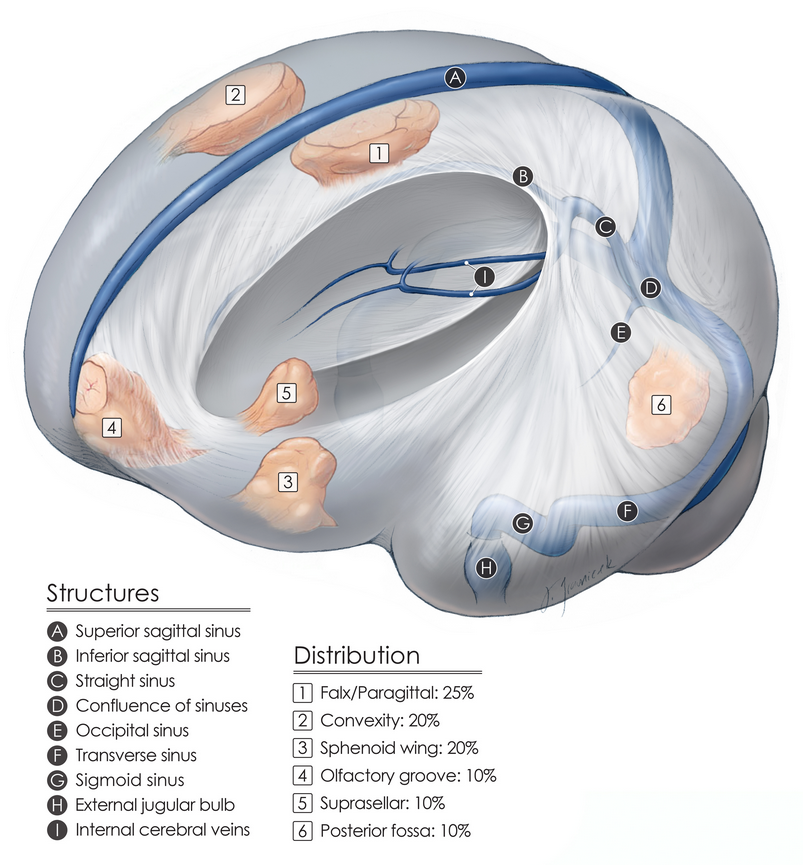

How Is It Diagnosed?

Your physician has many methods available to aid in the diagnosis of a meningioma. He or she will integrate information from the patient's clinical history, physical examination, and/or radiological evaluations to eliminate other possible explanations and establish the correct diagnosis.

The first step is generally a neurological exam. The physician will test the patient’s vision, hearing, coordination, mental abilities, and reflexes. On the basis of these results, the physician will order additional tests. Some of the more common tests include:

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)—MRI enables the physician to examine soft tissues in more detail. A contrast dye might be used to specifically highlight abnormal structures within the brain.

- Computed tomography (CT)—a CT scan is used to differentiate structures on the basis of their density. Contrast dye may be used to highlight the tumor or brain vasculature.

- Angiography—angiography is often used preoperatively if the surgeon believes that major blood vessels are feeding the tumor or are contained within the tumor.

Figure 3. MRI of a large meningioma.

During the tumor-removal surgery, a biopsy is performed for testing and identification to confirm the final diagnosis of meningioma and its growth rate. Examination of the sample by a pathologist can confirm the diagnosis to classify the type of meningioma.

What Are the Treatment Options?

Treatment for a meningioma varies from person to person and depends on the tumor's size, location, and rate of growth, as well as the patient's age and overall health status.

Because of the slow-growing nature of meningiomas, many physicians prefer to leave small asymptomatic tumors untreated and monitor the tumor’s growth annually with MRI. Other treatment options include surgery and/or radiation therapy.

Surgery

Surgery is the method of choice for most meningiomas. Because meningiomas originate from the membranes surrounding the brain and not within the brain itself, they tend to be more clearly defined and easier to remove than infiltrative tumors such as gliomas.

The operation involves a craniotomy, during which the surgeon makes an incision in the scalp and removes part of the skull to gain access to the tumor. Surgery specifics vary greatly depending on the tumor's size and location.

Figure 4. Craniotomy (left) and surgical removal (right) of a meningioma.

Meningiomas at the base of the skull near cranial nerves or important blood vessels are more difficult to remove, have a higher rate of complications, and may be amenable to only partial removal.

When total tumor removal is not surgically possible, the patient is observed periodically with MRI scans to carefully monitor the size of the residual tumor.

Radiation therapy might be considered after surgery. Surgery along the skull base requires a neurosurgeon with subspecialty training in skull base surgery.

For patients with increased intracranial pressure caused by the blockage of cerebrospinal fluid flow (a condition known as hydrocephalus), the surgeon might also install a thin tube (called a shunt) to drain the extra fluid into the abdominal cavity, where it can be reabsorbed.

Possible risks of surgery include infection, bleeding, and additional neurological damage, including weakness and numbness.

Radiation

Radiation therapy can come in the form of traditional external-beam radiation or the more precise stereotactic radiosurgery (for example, Gamma Knife, Novalis, CyberKnife).

Traditional external-beam radiation therapy delivers a single beam of radiation directly to the tumor. The procedure is usually performed 5 times per week for several weeks. The risk of radiation damaging normal cells in adjacent neural structures exists. However, overall negative effects are rare.

Stereotactic radiosurgery can deliver higher doses of radiation more accurately by using precise computer imaging and multiple beams to target the tumor. It does not require any incision and is done as a single-session outpatient procedure.

Unlike external-beam radiation, surrounding structures are not as prone to damage from the radiation treatment. This method might be better for tumors near important brain structures.

Depending on the tumor size, grade, and location, the surgeon or oncologist might recommend radiation therapy, even in cases for which resection is thought to be nearly complete. This treatment stops the growth of residual tumor and prevents recurrence.

Possible complications of radiation therapy include headaches, seizures, neurological problems (depending on the area being treated), and difficulties with thinking or decision-making.

In rare cases, injury of healthy tissues caused by radiation (radiation necrosis) is another possible but delayed complication of radiotherapy that results in headaches, memory loss, personality changes, and seizures. This complication can occur months to years after treatment.

Meningioma Prognosis: What Is the Recovery Outlook?

The recovery outlook for a meningioma depends on the tumor grade (aggressiveness), size, and location, as well as the patient's age and overall health.

The survival rate is usually excellent for patients with a benign meningioma in a surgically accessible location, with approximately 90% of patients surviving at 10 years.

Low Grade Meningiomas

Low-grade meningiomas, also known as benign or grade 1 meningiomas, are slow-growing tumors with cells resembling normal ones. They have a favorable meningioma prognosis and account for the majority of cases.

Most patients with low-grade meningiomas enjoy a high 5-year survival rate, exceeding 70-80%. These tumors can often be completely removed through surgery, and the chances of recurrence are low.

High Grade Meningiomas

High-grade meningiomas, which include grade 2 (atypical) and grade 3 (malignant or anaplastic) tumors, are more aggressive and tend to invade nearby tissues or recur after treatment. The 5-year survival rates for high-grade meningiomas are lower, generally around 50-60% for grade 2 and significantly less for grade 3.

Living With Meningioma

Living with a meningioma varies from one person to another. Many patients with low-grade tumors may experience few symptoms, if any, after treatment.

Conversely, for those with high-grade meningiomas, the journey can be marked by significant changes, including regular therapies and follow-up appointments. They may also experience neurological symptoms depending on the tumor location.

A key aspect of coping with meningioma is having a solid support system and access to resources such as support groups. As treatments can affect physical and cognitive functions, rehabilitation services such as physical, occupational, and speech therapy might be integral to aid recovery and adaptation.

Resources

Glossary

Cerebrospinal fluid—clear fluid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord

Craniotomy—a procedure to open and temporarily remove a piece of bone from the skull to expose the brain

Hydrocephalus—accumulation of fluid within the brain

Meninges—three membranous layers (dura, arachnoid, pia) that cover the brain and spinal cord

Primary brain tumor—tumors that originate in the brain, as opposed to those that have spread from other parts of the body to the brain

Stroke—a condition that occurs when blood supply to a part of the brain is interrupted or reduced, which prevents the delivery of oxygen and nutrients to brain tissues

Ventricles—network of cavities within the brain filled with cerebrospinal fluid

Contributor: Gina Watanabe BS

References

- Ostrom QT, Patil N, Cioffi G, et al. CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2013–2017. Neuro-Oncology 2020;22(Suppl 1):iv1–iv96. doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/noaa200

- Wiemels J, Wrensch M, Claus EB. Epidemiology and etiology of meningioma. J Neurooncol 2010;99:307–314. doi.org/10.1007/s11060-010-0386-3

- Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Kruchko C. Meningiomas: causes and risk factors. Neurosurg Focus 2007;23:E2. doi.org/10.3171/FOC-07/10/E2