Overview of Arteriovenous Malformation

Overview

An arteriovenous malformation (AVM) is an abnormal tangle of blood vessel connections between arteries and veins that disrupts blood flow and oxygen delivery to nearby tissues. General symptoms include headaches and seizures.

However, most AVMs do not produce symptoms until bleeding occurs. A sudden and severe headache often described as the “worst headache of my life” might indicate an AVM rupture in the brain. Severe back pain, weakness, or paralysis can occur with AVM bleeding in the spine. Treatment options include observation, surgery, radiosurgery, and endovascular embolization or a combination of these options.

What Is an Arteriovenous Malformation?

An AVM is a tangle of abnormal blood vessel connections between arteries that carry oxygen-rich blood toward tissues and veins that carry oxygen-depleted blood away from tissues. Normally, small blood vessels only 1 cell thick exist between arteries and veins. These vessels are called capillaries, and they slow the passage of blood to provide enough time for oxygen to move from blood to tissues. In AVMs, the absence of capillaries in the area allows blood in high-pressure arteries to rush directly into low-pressure veins. These veins stretch and become enlarged with incoming blood, weakening the vessel walls. Symptoms often do not occur until the AVM ruptures and bleeds.

Why should you have your surgery with Dr. Cohen?

Dr. Cohen

- 7,000+ specialized surgeries performed by your chosen surgeon

- More personalized care

- Extensive experience = higher success rate and quicker recovery times

Major Health Centers

- No control over choosing the surgeon caring for you

- One-size-fits-all care

- Less specialization

For more reasons, please click here.

Figure 1: A large AVM with arteries colored in red and veins in blue. Early and abnormal mixing of arterial and venous blood is shown in purple.

What Are the Symptoms?

General symptoms of AVMs include headaches and seizures. However, most AVMs do not produce symptoms until bleeding occurs. Blood from a ruptured AVM can enter the space contained within the skull and push against brain tissue, causing a sudden and severe headache often described as the “worst headache of my life.” In the case of spinal AVMs, sudden and severe back pain, weakness, or paralysis can indicate AVM bleeding.

What Are the Causes?

AVMs do not have a well-defined cause but are often present at birth. They are usually not hereditary, but some cases are associated with other abnormalities such as Osler–Weber–Rendu disease and Sturge–Weber syndrome.

How Common Is It?

AVMs are rare and have been estimated to affect less than 1% of the general population. Bleeding of an AVM accounts for 2% of all strokes. Symptoms are seen more commonly in patients between the ages of 20 and 40 years.

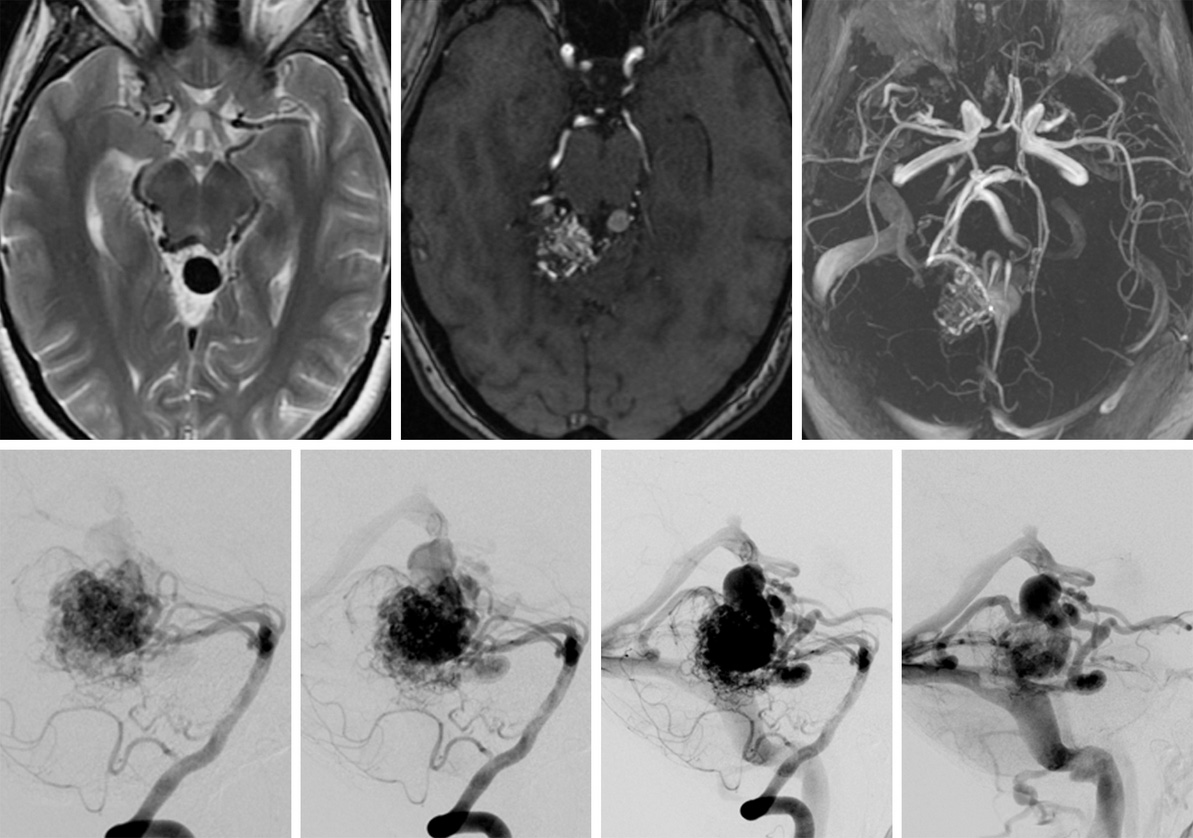

How Is It Diagnosed?

AVMs are usually diagnosed by magnetic resonance imaging and angiography, a minimally invasive procedure that involves placing a catheter into an artery, passing it through blood vessels to the brain, then injecting a contrast dye. X-ray images and videos are then taken to visualize the structure of the blood vessels and blood flow from arteries to veins.

Figure 2: Magnetic resonance (top left) and magnetic resonance angiographic (top middle and top right) images of a brain AVM. (Bottom Left to Right) Angiographic images of blood flow as it passes from arteries to veins.

What Are the Treatment Options?

AVM treatment options include surgical resection, radiosurgery, and embolization or a combination of these options. The increasing use of imaging has allowed for greater detection of unruptured AVMs. Such AVMs, especially if they do not produce symptoms, can be monitored if treatment options pose a greater risk than the risk of rupture when observing the AVM over time. The risk of AVM rupture is approximately 2% to 4% every year and can be fatal if not treated promptly. Patients are at higher risk of AVM rupture if they have history of a previous AVM bleed.

Observation

Patients with no history of AVM bleeding can be observed over time with treatment of their symptoms. This option might be preferred in older patients with a lower cumulative lifetime risk of bleeding.

Surgery

Surgical resection involves creating an opening in the skull (called a craniotomy) to sufficiently expose the artery and veins involved in the AVM. The surgeon carefully dissects the AVM from the surrounding brain tissue and removes the AVM by disconnecting it from the involved arteries and veins. After an uncomplicated surgery, patients might stay in the hospital for 5 to 7 days. Surgery is an immediate cure for AVMs. However, not everyone with an AVM should undergo surgery. Large AVMs that are located next to sensitive brain structures and involve deeper veins in the brain make surgery more complex and increases the risk for complications.

One of the most serious complications during an operation is AVM rupture; heavy bleeding can be fatal. However, this complication is rare. The more common possible complications occur after the operation and include swelling of the brain (edema) and bleeding. Stroke and damage to areas of the brain that affect one’s ability to perform daily activities can also occur in a small percentage of patients.

In this video, Dr. Cohen describes the techniques for surgery to treat an arteriovenous malformation.

For more information about the technical aspects of the surgery and extensive experience of Dr. Cohen, please refer to the chapter on Nuances in AVM Resection in the Neurosurgical Atlas.

Radiosurgery

Radiosurgery aims hundreds of low-dose beams of radiation at the abnormal vessels of the AVM using technologies such as the Gamma Knife or Novalis. The goal is to injure the cells of the connecting vessels periodically until scar tissue forms; scar tissue can close off the blood supply to, and eventually shrink, an AVM. The procedure is painless; it can take several hours of preparation and 1 hour for delivery of the radiation itself. The patient can go home the same day.

Treatment can take 1 to 3 years to destroy the AVM completely. During this time, there is still a risk of AVM rupture and bleeding. Radiosurgery is often recommended if the AVM is less than 3 cm in diameter and/or located in a sensitive area of the brain in which surgery could cause neurological problems. For small AVMs less than 3 cm in diameter, the cure rate is up to 90%.

Possible complications of radiosurgery include nausea, vomiting, seizures, and headaches. Several complications, such as hemorrhage, death of healthy tissue around the site of radiation (radiation necrosis), and brain swelling (edema) can occur weeks to years after treatment.

Embolization

Embolization uses the same initial procedure as diagnostic angiography, in which a catheter is passed through an artery at the top of the leg and then guided to the blood vessels of the AVM. Instead of injecting a contrast dye, an occluding material such as a special glue is delivered to the blood vessels of the AVM to block off blood flow. The procedure can take 3 to 8 hours and is followed by at least an overnight hospital stay. The length of stay varies, and the patient might stay in the hospital for several days while being observed. Although this is a less invasive option than surgery, it can be used to treat AVMs that are deeper in the brain and harder to access. Multiple treatments might be necessary to obliterate the AVM; however, this procedure is not considered curative.

Possible complications of embolization include stroke and rebleeding if blood flow to the AVM is not completely blocked off. Embolization is often used in combination with surgery or radiation.

What Is the Recovery Outlook?

Complete cure is possible by removing the AVM through surgery or closing off blood supply to the AVM through radiosurgery and embolization. A combination of these procedures might be necessary. After surgery, it can take 4 to 6 weeks for the patient to go back to performing his or her usual activities, and full recovery requires up to 2 to 6 months. However, the speed of recovery for each person varies. If the surgery affects a patient’s speech or ability to perform daily activities, his or her doctor might recommend working with a speech or occupational therapist.